From then on, it seemed there was no waking or sleeping,

and I just don't know which day was which.

Jack had told me right away

and some people had said for their wives to go away...

And I remember saying -- well, I knew if anything happened,

we'd all be evacuated to Camp David or something.

JFK & JACKIE CUBAN MISSILE LOVE STORY

But I said, "Please don't send me away anywhere.

If anything happens, we're all going to stay right here with you.

Even if there's not room in the bomb shelter in the White house -- which I'd seen.

Please, I just want to be on the lawn when it happens --

I want to die with you, and the children do too -- than live without you."

So he said he wouldn't send me away.

And he didn't really want to send me away, either.

JFK and Jackie were famously very private people when it came to openly expressing their love for each other in public or even among friends and family. It was obvious they were in love -- you could tell by their words and deeds -- but both were very strong emotionally -- Jackie even moreso than JFK -- recall her strength and composure after the assassination -- how she held herself together for the sake of the nation. JFK and Jackie had been through ecstasy and agony together -- the highest highs -- JFK winning the presidency, and the lowest lows -- losing two children born prematurely.

Although Jackie seemingly kept very much in the background politically -- focusing instead on their children and artistic and cultural projects as First Lady -- it has been learned all these years later that Jackie was in fact much more involved in sharing JFK's burdens of office than people realized.

Below are photos from various books* inserted into pertinent passages from two books (one of them taped interviews of Jackie herself) that describe how much JFK depended on his wife for emotional and intellectual support during the Cuban Missile Crisis -- one of the most serious, of many crises, that JFK was hit with during the two years and ten-months of his presidency. Just as Jackie had been JFK's rock of Gibraltar during his near-death back surgery and seven-month recovery in 1955 -- never leaving his side for a moment -- so too was she his rock during those thirteen days in October 1962 -- their bond forged, like steel, through fire. ~ Jackie Jura

THE KENNEDY WHITE HOUSE FAMILY LIFE & PICTURES, 1961-1963

by Carl Sferrazza Anthony (2001), pages 197-200

..."There was a little squib...in the New York Times. It said that 'at four o'clock in the afternoon, the President had called up Mrs Kennedy and they went and walked out in the rose garden'", recalled Chuck Spalding. "He was sharing with her the possible horror of what might happen." No less a person than the president's military aide, Major General Chester Clifton, later confessed, "JFK turned to his wife for advice whenever a crisis arose...he would talk to her about it and she would talk with him. She wouldn't advise his staff, she would advise him -- that's why nobody knew about it". The British ambassador remembered having a meeting at the time of the crisis with the president. Since the ambassador was also a discreet personal friend of the president's, the presence and participation of the First Lady in their talks would raise no red flags. "Jackie told me she took notes when Jack and I talked about this," he later recalled.

When the president was about to helicopter away from the White House in the midst of the crisis, Dr Janet Travell found it strange that the 'copter suddenly lowered, the back door opened, and Jack emerged. Then she noticed a figure with "hair wild in the gale of the rotors" who began racing across the lawn to the president. It was his wife. "She met him almost at the foot of the helicopter steps and she reached up with her arms. They stood motionless in an embrace for many seconds", Travell recorded in her diary entry for Friday, October 19. "Then she returned under the awning and he was away. Perhaps no one else noted that rare demonstration of affection. A few days later in the publicized hours of the Cuban Missile Crisis, I remembered it. I thought of its deep significance -- the unbreakable bond of love between them that showed clearest in times of trouble".

That Jackie flatly refused to take the pink tickets necessary for entry for herself and the children to an emergency shelter at a Defense Department installation in rural Virginia was the most tangible proof of her unconditional love for the president.

It must have shocked yet heartened him. As Kenny O'Donnell remembered, the First Lady simply "refused to leave him alone in the White House". After this decision, Jack seems to have made his wife a full political partner and confidante, if only in this crisis.

"Maybe it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis when husband and wife meant the most to each other," a Time reporter observed. "He would tell her everything that was happening". What she told him, unfortunately, was left unrecorded. It is possible, however, that she offered practical advice based on human psychology. She had carefully observed the Politburo members during the 1961 Vienna meeting with Khrushchev and felt that only Gromyko could be taken at his word. She offered this impulse based on her keen ability to size up public personas and the people behind them.

Jackie's "reports", as one senator characterized her letters to the president following her meetings with foreign leaders, were, he said, "full of subtle political observation...that held back nothing by way of praise or criticism". In all likelihood, Jackie posed to Jack the timeless questions of human motivation and suggested he consider the emotions, rational strategy, and fears of the Soviets as he made decisions. Whatever she said, it seemed to go beyond mere wifely emotional support at a time of crisis. In later acknowledging those he considered to be his most trusted advisers with a symbolic gift as a reminder of the crisis they shared, he included Jackie among the recipients.

That he reached out to her in this crisis was an important personal turning point for Jack, a breakthrough of sorts. "If it was earlier in their marriage, I don't think he would have called her then," Chuck Spalding affirmed.

Throughout this time, the most dangerous period of the Kennedy administration and the world at large, Jack depended upon other members of his family. His single most crucial advisor was the attorney general.

When photographs from reconnaissance planes proved without a doubt that the Soviet Union was sending ships to Cuba, it was feared that they were carrying offensive materials and missiles.

The president established three specific plans of reaction:

-- let the ships through;

-- establish a naval blockade;

-- destroy existing Cuban missile sites and invade the island.

It was Bobby Kennedy who vehemently urged against the invasion alternative, advice completely counter to what most military advisers were telling the president. His advice weighed heavily on the president's thinking. It was Bobby, against some formidable senior officials and experts in foreign affairs, who made the case for Slow Track, the blockade of the Soviet ships, as opposed to Fast Track, which called for bombing Cuba and, he feared, potentially setting off retaliation by Khrushchev.

It was Bobby who met the Soviet ambassador and told him blankly:

"Agree to remove your missiles from Cuba,

unilaterally and unconditionally,

within twenty-four hours

or we will bomb them."

That night the two brothers dined together with Dave Powers. Jack said Powers ate as if it were his last meal. "I'm not so sure it isn't," cracked Powers....

Joe Kennedy [JFK's father] happened to be staying in the White House at the very time, his second of only three visits there. Jack and Bobby went into the Lincoln Bedroom to say good night to him. They kissed him.

Certainly his support, if not his advice on foreign relations, would have been greatly cherished at a moment like this.... Rather unusually, the president saw his father twice during the crisis. He slipped away, up to Hyannis Port, for some private reflection on the stretch of beach there, and held some meetings with military advisers in the ambassador's living room, which had windows facing the sea....

When the president addressed the nation, Rose Kennedy watched. Feeling desperately worried about her son, she cried openly -- which she rarely did, not even upon Joe's stroke.

When Jack ultimately decided on a blockade it became a waiting game with the Soviets. Even the best intelligence could provide only an educated guess about the possible reaction of the Soviets -- including nuclear retaliation. This led to an overwhelming national anxiety -- but not panic -- with concern that President Kennedy would make no missteps. It was precisely the sort of situation that called for cool detachment yet decisive action, necessitating absolute emotional stability. No matter how tough Kennedy was, he was first and foremost a human being. He depended on his wife as a foundation of advice on human behaviour, and could discuss the potential consequences of the crisis in a larger, even philosophical context of humanity. In his children, however, he found a personal motivation to safely resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On Monday morning, October 22, the president went into a very early meeting in the Cabinet Room. At one juncture, he took a breather and paced outside on the terrace. He noticed Caroline and her schoolmates playing on the lawn. He gave his special signal to her -- two loud claps -- that usually evoked an immediate response. This time, however, Caroline was delayed and Jack went back into his meeting. A few minutes later, Caroline ran into the Oval Office. "Where's my daddy"? she asked Mrs Lincoln. She was told that the president was in a serious meeting and could not be interrupted, "But I have to", she whined, just before she darted into the Cabinet Room and blurted out to the room of military and political advisers, "Daddy, I would have come sooner, but Miss Grimes wouldn't let me go".

After his broadcast to the nation on the missile threat, Jack went upstairs to read stories to Caroline. Then he and his wife ate dinner alone together. At one point during the thirteen-day standoff, Powers watched him sadly reading at night to Caroline. "If it weren't for the children, it would be so easy to press the button", Jack said to Dave Powers. "Not just John and Caroline, and not just the children of America, but children all over the world who will suffer and die for the decision I have to make".

Although he rarely expressed his religious convictions, during the crisis Jack did try to go unnoticed to St Matthew's Church with Dave Powers.

In the last pew of the church, they prayed together. Throughout the crisis, he found the most solitary peace in his Rose Garden.

When it was clear that the Soviets were backing down and that there would be no missile launchings, he wrote to his wife's friend Bunny Mellon, the horticulturalist who had designed the site for him: "I need not tell you that your garden has been our brightest spot in the somber surroundings of the last few days"....

JACQUELINE KENNEDY: HISTORIC CONVERSATIONS

ON LIFE WITH JOHN F KENNEDY (2011)

Interviews recorded in 1964 with Arthur Schlesinger, Jr,

pages 261-267

Background: On Tuesday morning, October 16, 1962, Bundy [National Security Assistant] told the President in his White House bedroom that U-2 photography by the CIA had revealed the Soviets installing offensive missiles in Cuba -- an eventuality that JFK had assured the public the previous month that he would never accept. Midterm congressional elections were three weeks ahead. Anxious to keep the missile problem secret from Americans until he and his advisers agreed on a strategy, Kennedy tried to maintain his normal schedule, flying to Chicago for a campaign address, before returning to Washington on the pretext that he was suffering from a cold. On Monday evening, October 22, JFK gave his television speech announcing that his "initial step" would be to throw a naval blockade (euphemized as a "quarantine") around Cuba and demand the missiles' removal....

SCHLESINGER ASKS: How early were you told about the missiles? It was not in the papers. The news arrived on a Tuesday and then the small -- very small group knew. And he went away on the Friday -- -- and then came back on the Saturday, and then gave his speech on the Monday following.

JACKIE ANSWERS: Well, I can't remember if I knew before -- but I'm sure I would have known if he was worried or something. But I can remember so well, I'd just gotten down to Glen Ora with the children and it was a Saturday afternoon -- and I'd just sort of gotten there, and I was lying in the sun and it was so nice to be there, and this call came through from Jack and he said, "I'm coming back to Washington this afternoon. Why don't you come back there?"

And, you know, usually he would be coming down -- or I thought he'd be away for the weekend -- or he would be coming down on a Saturday or I would have said, "Well, why don't you come down here?" or something. But there was just something funny in his voice and he never asked me to do -- I mean, he knew that those weekends -- away from the tension of the White House -- were so good for me, and he'd encourage me to do it. It was just so unlike him, having known I'd just gotten down there with two rather whiny children, who I'd have to wake up from their naps and get back. But I could tell from his voice something was wrong, so I didn't even ask. I said, sort of, "Why"? And he said, "Well, never mind. Why don't you just come back to Washington?" So I woke them up from their naps and we got back there, I suppose, around six or something. And then I guess he told me. I think that must have been when. But I just knew, whenever he asks, or I thought -- whenever you're married to someone and they ask something -- that's the whole point of being married -- you just must sense trouble in their voice and mustn't ask why. And so we came right back.

And then, those days were -- well, I forget how many there were -- were there eleven, ten something? But from then on, it seemed there was no waking or sleeping, and I just don't know which day was which. But I know that Jack -- oh, he'd said something -- I know he told me right away and some people had said for their wives to go away and Mrs Phyllis Dillon told me later that Douglas had taken her for a walk and told her what was happening, and suggested she go to Hobe Sound or somewhere. I don't know if she did or not. And I remember saying -- well, I knew if anything happened, we'd all be evacuated to Camp David or something. And I don't know if he said anything about that to me, I don't think he -- but I said, "Please don't send me away to Camp David" -- you know, me and the children -- "Please don't send me anywhere. If anything happens, we're all going to stay right here with you". And, you know -- and I said, "even if there's not room in the bomb shelter in the White house" -- which I'd seen. I said, "Please, then I just want to be on the lawn when it happens -- you know -- but I just want to be with you, and I want to die with you, and the children do too -- than live without you". So he said he -- he wouldn't send me away. And he didn't really want to send me away, either....

Well, then, as I say, there was no day or night because I can remember one night, Jack was lying on his bed in his room, and it was really late, and I came in in my nightgown.

I thought he was talking on the phone. I'd been in and out of there all evening. And suddenly, I saw him waving me away -- Get out, get out! I'd already run over to his bed -- and it was because Bundy was in the room. And poor Puritan Bundy, to see a woman running in in her nightgown! He threw both hands over his eyes. And he was talking on another phone to someone. Well, then I got out of the room and waited for Jack in my room, and whether he came to bed at two, three, four, I don't know.

And then another night, I remember Bundy at the foot of both our beds, you know, waking Jack up for something. And Jack would go into his own room and then talk on the phone maybe until, say, from five to six to seven. And then he might come back and sleep for two hours and go to his office, or -- as I say, there was no day or night. And, well, that's the time I've been the closest to him, and I never left the house or saw the children, and when he came home, if it was for sleep or for a nap, I would sleep with him. And I'd walk by his office all the time, and sometimes he would take me out -- it was funny -- for a walk around the lawn, a couple of times. You know, he didn't very often do that. We just sort of walked quietly, then go back in. It was just this vigil.

And then I remember another morning -- it must have been a weekend morning -- when all -- there was a meeting in the Oval Room and everybody had come in one car so that the press wouldn't get suspicious. And Bobby came in in a convertible and riding clothes. And so, you know, and I was there -- so -- and then I went in the Treaty Room, where I -- well, just to fiddle through some mail or something, but I could hear them talking through the door. And I went up and listened and eavesdropped. And I guess that was at a rather vital time, because I could hear McNamara saying something, "I think we should do this, that, this, that." No -- McNamara summing up something and then Gilpatric [Assistant Secretary of Defence] giving some summary and then a lot of questions -- and then I thought, well, I mustn't listen and went away.

SCHLESINGER ASKS: Did the President comment at all on the question of whether there would be a raid to knock the bases out or blockade or what?...

JACKIE ANSWERS: Well, that I knew later -- that was never told to me until much, much later. And the thing was -- no, at the time, you know, at the time he -- well, it was just so -- he really wasn't sort of asking me. But then I remember he did tell me about this crazy telegram that came through from Khrushchev one night. Very warlike.

I guess he'd sent the nice one first where he looked like he would -- Khrushchev had -- where he might dismantle, and then this crazy one came through in the middle of the night. Well, I remember Jack being really upset about that and telling me -- and then deciding that they would just answer the first -- and being in on that.

I also remember him telling me about Gromyko [Soviet Foreign Minister], which was very early in it -- how he'd seen Gromyko and he talked to him -- and everything they'd said -- and that he really wanted to put Gromyko on the line for just lying to him -- and never giving anything away. And I said, "How could you keep a straight face?" or "How could you not say, 'You rat!' sitting there? And he said, "What, and tip our whole hand?" So he described that to me.

And then I remember another thing -- one of the worst days of it all, the last day -- suddenly some U-2 plane got loose over Alaska -- violated Soviet airspace -- or some awful thing. Oh, my God, you know, then the Russians might have thought we were sending it in, and that could have just been awful...

And then I remember just waiting with that blockade. The only thing I can think of what it was like, it was like an election night waiting, but much worse. But one ship was coming and some big fat freighter had turned back, but it didn't have anything but oil on it anyway -- and all these ships cruising forward.

And I remember hearing that the Joseph P Kennedy was there [destroyer named after JFK's brother] and saying to Jack, "Did you send it?", or something. And he said, "No, isn't that strange? -- and then finally, when it was over, saying to me -- and Bundy saying to me either then or later -- that if it had just gone on maybe two more days, everybody really would have cracked, because all those men had been awake night and day....everyone had worked to the peak of human endurance.

SCHLESINGER ASKS: Did the President show fatique?

JACKIE ANSWERS: Well, as the days went on, yes. But he always -- you didn't worry about him and fatigue because you'd seen him driving himself so much all his life -- I mean, through some awful campaigns and bone tired, and getting up at five to be at a factory gate and still -- So you knew he always would have some hidden reserve to draw on. But, oh, boy, toward the end -- you always think -- I always think that if you're told how much longer you have to go on, you can always make it. But the awful thing with then was you didn't know. And finally, when it was over, I mean, I don't know how many days or weeks later it was, but he thought of giving that calendar to everyone. And he worked it out so carefully himself.

And then it was a surprise. I didn't -- I was so surprised when I got one because he told me he wanted to do it so he said, you know, "Ask Tish or Tiffany," or something. So I told her and then when they came, I was so surprised that I had one and I burst out crying....

watch Kennedy Address to Nation on Cuban Missile Crisis, October 22, 1963

JACKIE'S TREASURES: THE FABLED OBJECTS: She was simply who she was, part of the fabric of American culture. In grand circles, the word 'class' is considered a bad-taste word, but class is really the key word to describe her. Style, chic, and other such attributes are acquirable; class is not. Either you have it or you don't. Jackie had it in spades.

JACKIE'S TREASURES: THE FABLED OBJECTS: She was simply who she was, part of the fabric of American culture. In grand circles, the word 'class' is considered a bad-taste word, but class is really the key word to describe her. Style, chic, and other such attributes are acquirable; class is not. Either you have it or you don't. Jackie had it in spades.

First Lady Biography: Jackie Kennedy, age 31 (January 20, 1961 - November 22, 1963)

...At an early age, Jacqueline Kennedy wrote essays and poems which were sometimes published in local newspapers. In her high school newspaper Salmagundi, she penned a cartoon series and won the graduating award for literature. In 1951, she submitted an entry to Vogue magazine's Prix de Paris contest, the prize for which was to spend half a year in New York, and the other half in Paris as a junior editor for the magazine. The submission was rigorous, requiring an original theme for an entire issue, illustrations, articles, layout and design, an advertising campaign that could be tied into the issue's content. In the requisite essay, "People I Wish I Had Known," she listed playwright Oscar Wilde, poet Charles Baudelaire and ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev. Named one of the twelve finalists, she was then interviewed by the magazine editors and out of 1,280 entries she won the contest. Her mother, however, did not want her to leave the U.S. and made her turn down the prize. After college, she worked for the Washington Times-Herald as its Inquiring Camera Girl, earning $42.50 a week. Her job was to both photograph and interview local citizens with one question each day; her first interview was with Pat Nixon and others included Vice President Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy whom she later married. The questions became increasingly political, including topics like the Soviet Union, the Korean War, and the U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. One of her last assignments was to cover Queen Elizabeth's 1953 coronation.

...Contrary to the image of "lovely inconsequence" that her friend, historian Arthur Schlesinger characterized her as feigning, Jacqueline Kennedy had an intense interest in the substantive issues faced by the Administration; she kept this covert, however, believing that public knowledge of her views would distract from the uncontroversial historic and arts projects she adopted. Privately, she was known to provide the President with withering assessments of political figures with whom he was negotiating, whether it was Pentagon brass or the Soviet Politburo. After the Bay of Pigs, Jacqueline Kennedy made a speech in Spanish, in Miami, December 1962, to the brigade of Cuban fighters who had landed in Cuba to carry out the ill-considered operation. Throughout the days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, she remained at the President's side and he kept her informed of each top-secret move that the U.S. and Soviet Union were making; afterwards, in thanks for the emotional support she provided to him, he presented her with one of the same silver calendars commemorating the crisis that he gave to his military advisors who had helped him. As the fight for civil rights of African-Americans gained momentum, the First Lady illustrated a subtle support for it; when she created a kindergarten in the White House for her daughter and a few select youngsters, it was racially integrated and photographs of the group were publicly released. Jacqueline Kennedy made more international trips than any of her predecessors, both with the President and on her own: France, Austria, England, Greece, Venezuela and Colombia in 1961, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Italy and Mexico in 1962, Morocco, Italy, Turkey, Greece, France in 1963. On many of these trips, she forged personal friendship with world leaders, including France's Charles DeGaulle, India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Pakistan's Ayub Kahn, England's Edward McMillan, subtly furthering the interests of the President and the U.S. In South American nations, for example, she made speeches in Spanish hailing the promise of the Administration's Peace Corps. Believing that Kennedy's most important accomplishment was his 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, days after his assassination she penned a remarkable letter to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, calling on him to remain committed to nuclear arms reduction and urge smaller nations to do likewise....

watch Senator John Kennedy recovering from spinal surgery, December 21, 1954

JOHNNY, WE HARDLY KNEW YE, by Kenny O'Donnell & Dave Powers (1970)

JOHNNY, WE HARDLY KNEW YE, by Kenny O'Donnell & Dave Powers (1970)

...All of that summer of 1954, when he was forced to sit on the sidelines with his despised crutches, watching, instead of playing in, the touch football and baseball games at Hyannis Port, Jack argued with his doctors about whether he should undergo the spinal fusion surgery. His only hope of getting relief from pain was a removal of the metal disc that had been placed in his spine by Navy surgeons in 1944 and a remending of the separated vertebrae. The Kennedy family's physician, Dr Sara Jordan, and her colleagues at Boston's Leahy Clinic were opposed to such an operation, or any kind of an operation, because he was suffering from an adrenal insufficiency, which increases the possibility of shock and infection during surgery. He was warned that his chances of surviving the operation were no better than fifty-fifty. He was determined to take the risk. Pounding his fist on his crutches, he said, "I'd rather be dead than spend the rest of my life on these things."

He entered the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York where he went through a long and difficult operation on October 21. As expected, infection set in, and twice during the next month he was so close to death that his family was summoned and he was given the last rites of his church. Then he rallied, and on December 20 with Jackie at his side he was taken to a plane on a stretcher and flown to the Kennedy home at Palm Beach for Christmas holidays, with the hope that he might improve in those pleasant surroundings. But within a month he was back in the same hospital again, undergoing a second operation, which was more successful. Late in February, Ambassador Kennedy called Dave Powers and asked him to come to the hospital and to fly to Palm Beach with Jack, Jackie and Ted. Before Jack was taken from the hospital, Dave watched the dressing on the surgical wound being changed. "He had a hole in his back big enough for me to put my fist in it up to the wrist," Dave says.

Dave spent the next five weeks at the Palm Beach waterfront home with Jack and Jackie. "He never said one word about what he went through at the hospital," Dave says. "He was in constant pain all the time I was there, unable to sleep for more than an hour or two at a time, but he never complained about the pain, never mentioned it. The Ambassador, who was there with us all the time, would say to me often, "Dave, don't try to give him anything for the pain -- it's something he has to go through.' I supposed he was afraid I might try to slip him a dose of sedative or a drink of whiskey. Jackie was with him all day and all night. He was in a room off the patio beside the pool to get a little sun. Jack would say, 'Dave is here if I need anything.' But she seldom left his bedside. Every Thursday, the cook's day off, the Ambassador would go into the kitchen and make a terrific lamb stew for our dinner."

When the Senator arrived at Palm Beach, Dave noticed that his room was crowded with several cartons of books from the Library of Congress. Back in January, before he returned to New York for the second operation, he had worked to pass the time in bed on a magazine article on political courage which he had been thinking about for more than a year....When Kennedy returned to Palm Beach for his long convalescence ater the second spinal oepration in February, he decided to expand the magazine article into a book, which became his Pulitzer Prize-winning Profiles in Courage. The plan for the book that he had in mind called for an enormous amount of reading and research.... Unable to sleep for more than an hour or two at a stretch, Jack worked on the book day and night, reading, and writing notes and then drafts of the chapters on long yellow legal pads. He clung to the research work doggedly, keeping his mind on it to distract himself from his pain. When he was too tired to write or read, Jackie and Dave read to him...

Early in March, about a week after his return to Palm Beach, Jack was able to get out of his bed and walk without his crutches for a distance of fifty feet from his room to a chair on the patio ouside beside the pool with Jackie and Dave beside him. "You never saw anybody more pleased," Dave says. "then, the next day, he walked all the way from the pool across the lawn to the beach and down to the edge of the water. He stood there, feeling the warm salt water on his bare feet, and broke into a big smile. The Ambassador was watching us from a window when Jack walked back to the house, leaning on Jackie and me. The Ambassador said to me later when we were eating lunch, 'God, Dave, he's getting stronger all the time. Did you see the legs on him? He's got the legs of a fighter or a swimming champion.' Then the Ambassador said, and I often thought of it later, 'I know nothing can happen to him now, because I've stood by his deathbed three times and each time I said good-bye to him, and each time he came back stronger.'"

On May 23, 1955, seven months after his first spinal surgery in New York, Kennedy arrived back in Washington from Palm Beach. He waved aside his crutches and the wheelchair that were waiting for him at the airport, went to the Capitol to pose for newspaper and television cameramen, and then walked unaided from the Capitol to his office in the Senate Office Building. The next day he was on the floor of the Senate, getting a big welcome from the two party leaders...

JFK'S HOME LIFE AT WHITE HOUSE

JFK & JACKIE CUBAN MISSILE LOVE STORY

(Jackie refused to leave JFK alone in White House)

JFK & JACKIE SHINING CAMELOT

(for one brief shining moment there was Camelot)

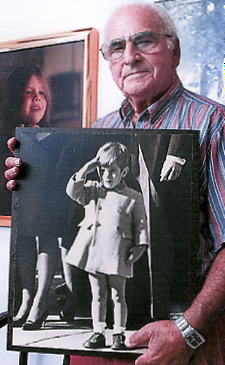

Photographer who captured John-John salute dies

(the shot seen around the world)

Irish/Annapolis/YouTube, Mar 3-8, 2012

watch John-John boarding Air Force One &

watch JFK YEARS OF LIGHTNING, DAY OF DRUMS

LITTLE SOLDIER JOHN-JOHN SALUTED JFK

JFK, JACKIE & BABY PATRICK

& 4.Old World Destruction

*photos scanned from books:

FOUR DAYS: THE HISTORICAL RECORD OF THE DEATH OF PRESIDENT KENNEDY, UPI/American Heritage, 1964

THE JOHN F KENNEDYS: A FAMILY ALBUM, Mark Shaw, Personal Photographer, 1964

THE KENNEDY YEARS, New York Times, Viking Press, 1964

JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY...AS WE REMEMBER HIM, family/friends/intimate associates, Columbia Records, 1965

ONE BRIEF SHINING MOMENT: REMEMBERING KENNEDY, William Manchester, 1983

LIFE IN CAMELOT, Little/Brown/Time Inc, 1988

JFK REMEMBERED: AN INTIMATE PORTRAIT BY HIS PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHER, Jacques Lowe, 1993

JACKIE'S TREASURES: THE FABLED OBJECTS, Dianne Condon, Cader Books, 1996

THE KENNEDY WHITE HOUSE, Carl Anthony, Touchstone Books, 2002

JOHN F KENNEDY BIOGRAPHY, Joyce Milton, AE/DK Publishing, 2003

JFK & JACKIE: UNSEEN ARCHIVES, Tim Hill, Parragon Publishing, 2003

JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY: A LIFE IN PICTURES, Phaidon Press, 2003

JACK KENNEDY: THE ILLUSTRATED LIFE OF A PRESIDENT, Chuck Wills, Chronicle Books, 2009