OZ COASTWATCHER EVANS RESCUED JFK

Evans meanwhile was watching anxiously from Gomu.

When, shortly before 6pm, his binoculars picked up the approaching natives,

he was dismayed not to see any Americans in the canoe.

Then it dawned on him that of course the natives would have concealed such a passenger.

When the canoe touched the sand,

Kennedy stuck his head through the palm fronds and smiled at Evans.

"Hello", he said "I'm Kennedy".

Evans introduced himself, and they shook hands.

"Come and have some tea."

...continued from O'REILLY BOOK KILLS JFK & EVANS

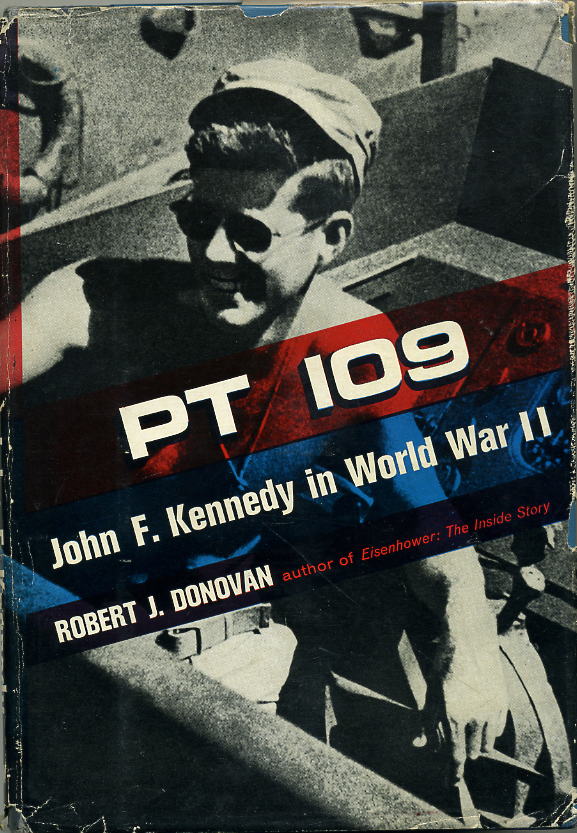

PT 109 -- JOHN F KENNEDY IN WORLD WAR II

by Robert J Donovan, published 1962

transcribed excerpts focus on the role of

Australian Navy Coastwatcher Lt Arthur Reginald Evans

in the rescue of American Navy Lt John Fitzgerald Kennedy & The Crew of PT 109

pages 129-211 with pics from various sources inserted to enhance understanding ~ Jackie Jura

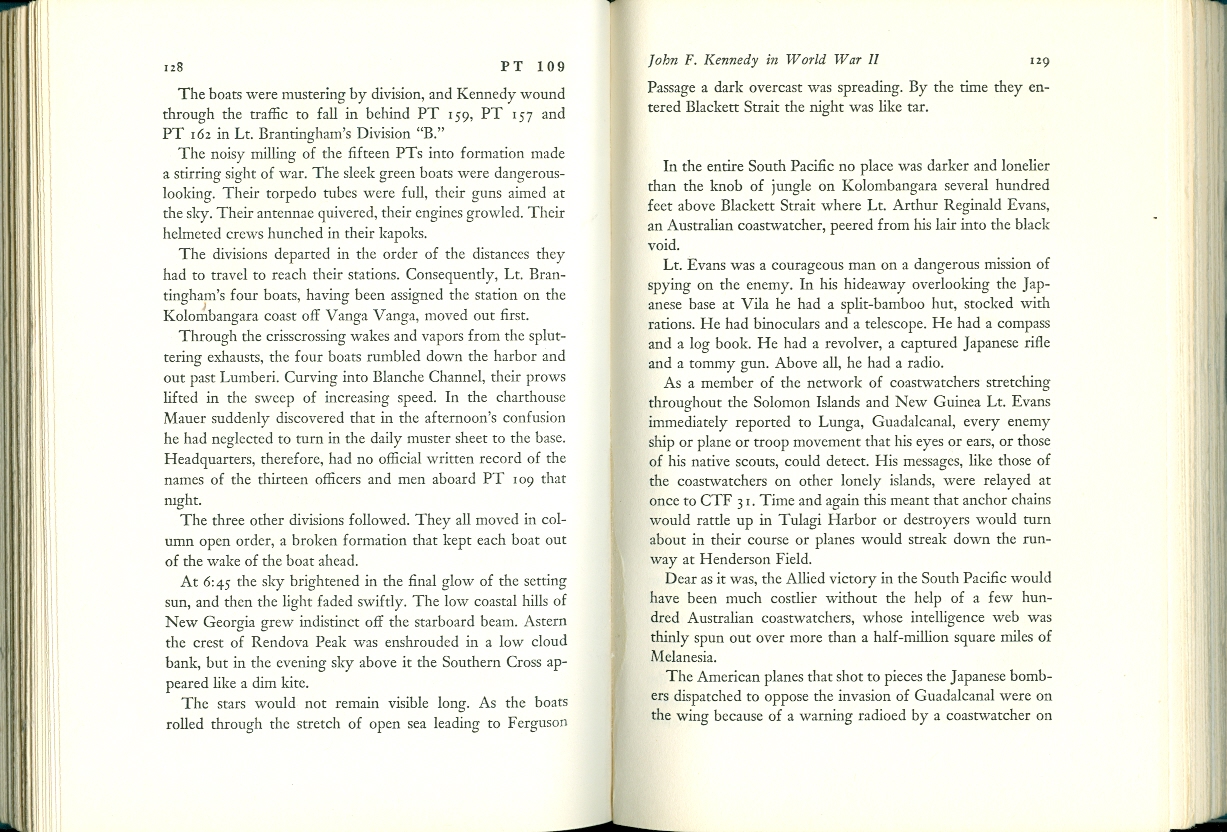

...In the entire South Pacific no place was darker and lonelier than the knob of jungle on Kilombangara several hundred feet above Blackett Strait where Lt Arthur Reginald Evans, an Australian coastwatcher, peered from his lair into the black void. Lt Evans was a courageous man on a dangerous mission of spying on the enemy. In his hideaway overlooking the Japanese base at Vila he had a split-bamboo hut, stocked with rations. He had binoculars and a telescope. He had a compass and a log book. He had a revolver, a captured Japanese rifle and a tommy gun. Above all, he had a radio.

As a member of the network of coastwatchers stretching throughout the Solomon Islands and New Guinea Lt Evans immediately reported to Lunga, Guadalcanal, every enemy ship or plane or troop movement that his eyes or ears, or those of his native scouts, could detect. His messages, like those of the coastwatchers on other lonely islands, were relayed at once to CTF31. Time and again this meant that anchor chains would rattle up in Tulagi Harbor or destroyers would turn about in their course or planes would streak down the runway at Henderson Field. Dear as it was, the Allied victory in the South Pacific would have been much costlier without the help of a few hundred Australian coastwatchers, whose intellingence web was thinly spun out over more than a half-million square miles of Melanesia.

The American planes that shot to pieces the Japanese bombers dispatched to oppose the invasion of Guadalcanal were on the wing because of a warning radioed by a coastwatcher.... Countless Allied airmen, who parachuted or crashed in the islands, and sailors whose ships went down, were rescued by the coastwatchers and their network of native scouts. The coastwatcher service was started just after World War 1 as a civilian enterprise, conceived and directed by the Australian Navy.... An important extension of the service was undertaken when Australian administrative officials in New Guinea and the Solomons were enrolled as coastwatchers. After Pearl Harbor the coastwatcher service became an arm of the Navy, and coastwatchers were spirited behind enemy lines by plane, submarine and native canoe. Every possible effort was made to conceal this apparatus from the Japanese, who hunted the individual coastwatchers mercilessly, sometimes with dogs. The code name for the organization was "Ferdinand", after Munro Leaf's lovable bull who liked to sit under a tree and smell wild flowers. Like Ferdinand, the coastwatchers were supposed to sit and gather information, not fight. Men like Lt Evans, however, were officers of the Australian Navy.

Reg Evans was a slight, brisk, lithe man with a fair complexion and a long, narrow face. He was cool of temperment, cultivated, and generously endowed with wit and charm. The son of a civil servant, he was born in Sydney on May 14, 1905, the eldest of three children. After attending state schools he went out to the New Hebrides in 1929 as an assistant manager of a coconut plantation. After a French company bought the plantation, young Evans returned to Australia and got a job with Burns Philp (South Sea) Company, Limited, traders and shippers. This time he was sent out to the Solomons where he held a variety of positions, including, for a couple of years, that of supercargo on the interisland steamer Mamutu. During these years Evans acquired a good deal of knowledge about the Solomon Islands and the Melanesian natives. He aslo acquired a wife, Gertrude Slaney of Adelaide, Australia, whom he met while she was vacationing with friends in Tulagi. When Evans became a coastwatcher, he chose his wife's initials, GSE, as his radio call letters, and thus Gertrude Slaney Evans won a footnote in the history of World War II.

At the onset of war Evans joined the Army and served for two years in the Middle East. It was not until July 1942 that he was transferred to the Navy and commissioned in the coastwatcher organization. After a stint on Guadalcanal he received orders in February 1943 to open a station on Kolombangara to which he moved by stages. A PBY picked him up at Florida Island and put him down in the darkness at Segi Point at the southeastern tip of New Georgia, which was still in enemy hands.

The coastwatcher at Segi Point was a tough, resourceful New Zealander named Donald C Kennedy. Donald Kennedy not only had a following of natives that had been capable of ambushing more than a hundred Japanese soldiers who had ventured too close to his lair but he also had a seagoing force that sailed in schooners. In his ten-ton "flagship" Dadavata he once rammed a Japanese whaleboat and blasted the crew with hand grenades. He and his men were credited with the killing of three bargeloads of enemy soldiers, the capture of twenty Japanese pilots and the rescue of twenty-two American pilots. Donald Kennedy got results from his standing offer to the natives of a bag of rice and some tinned meat for every downed pilot, Allied or Japanese, brought alive to his headquarters.

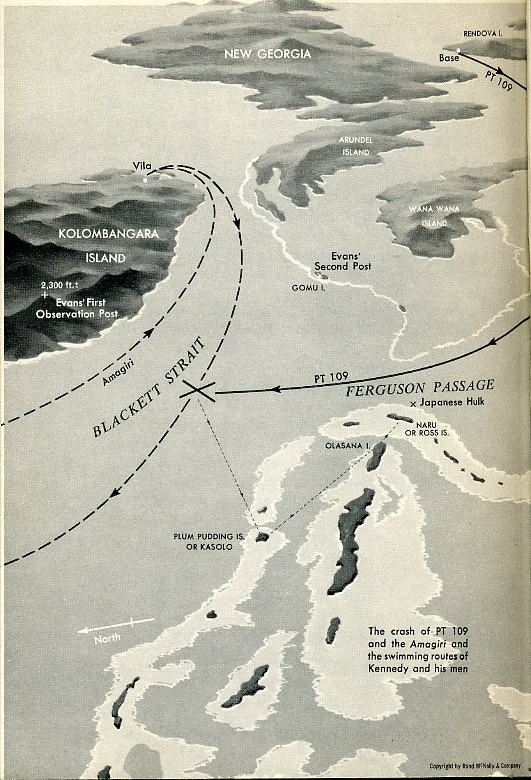

For two weeks Lt Evans took charge at Segi Point while Donald Kennedy visited Guadalcanal. Then on his return Evans embarked for Kolombangara in a dugout canoe with a native helper named Malanga, who had picked up some English in a mission school Traveling by night and hiding by day, they passed so close to the Munda airstrip that they could hear Japanese trucks in the darkness. Lt D C Horton, the coastwatcher on Rendova, had sent scouts to Kilombangara ahead of Evans to notify the natives he was coming. As a result a friendly delegation, including Rovu, the ancient headman, met him and built him the hut on the knob on the south shore. From this height he could look not only down upon Vila, but out across Blackett Strait and Ferguson Passage to Wana Wana and Gizo. He could, that is, when it was light. On this black night of August 1-2, 1943, he could see nothing but the dial of his watch...

Cruising back and forth across lower Blackett Strait, Commander Hanami, on the covered bridge of the Amagiri, was constantly worried that a PT boat, a destroyer or even a PBY would discover him. While the islands around him were held by his own troops, these narrow waters were treacherous for Japanese ships. Anywhere he turned Commander Hanami knew that an American man-of-war might be waiting. Navigating in the dark was dangerous because of the reefs. There were no adequate charts for this area of the Solomons. Furthermore, the Amagiri carried no radar. To a degree this disadvantage was offset by a group of trained lookouts who searched the darkness through ten affixed, wide-angle night binoculars.... Commander Hanami ordered the coxswain to head northwestward at increasing speed to rejoin the destroyers Hagikaze, Arashi and Shigure starting up the Kolombangara coast.

Approximately in his path several miles distant was PT 109, with Kennedy steering away from Kolombangara in a westerly direction toward Gizo, following PT 162 and PT 169. Kennedy had no orders other than to patrol of Vanga Vanga and look for whatever he could find. His mission boiled down to a matter of guessing where in the impenetrable blackness he might find a target. Encountering no sign of enemy ships in the middle of Blackett Strait, Kennedy made a fateful decision. He overtook Potter and Lowrey and suggested that the three boats reverse their direction.... The other two skippers agreed. The three boats turned about and with Kennedy now in the lead headed toward the southeast....

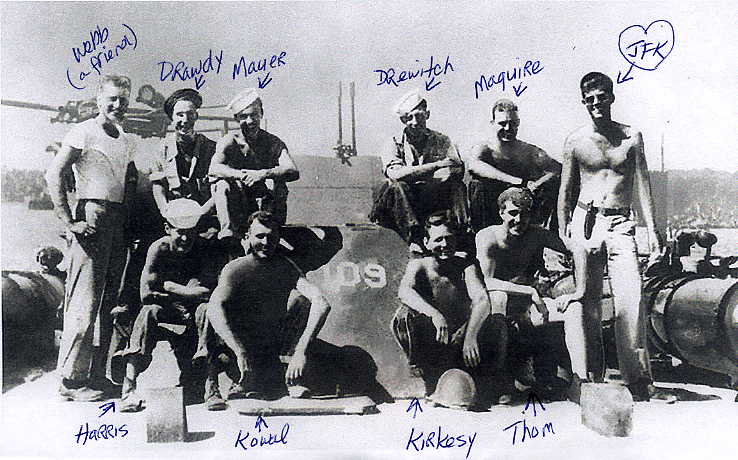

Aboard PT 109 Ensign Ross was standing on the foredeck by the 37-millimeter gun. Behind him was Kennedy at the wheel. At the skipper's right was Maquire and just beyond and above Maguire was Marney in the forward gun turret. On the skipper's left, outside the cockpit was Mauer. Aware that Kennedy still hoped to meet some of the other dispersed PT boats that must be wandering about the strait, Mauer was peering through the night for a familiar form. Albert was on watch amidships. Harris, off duty, was sleeping on the deck between the day-room canopy and a starboard torpedo tube. He had removed his kapok jacket and was using it as a pillow. McMahon was on watch in the engine room. Johnston was dozing on the starboard side of the deck near the engine-room hatch. Zinser was standing close by. Starkey was the lookout in the after gun turret. Kirksey, off duty, was lying aft on the starboard side. The boat was moving so quietly that Ross, scanning the dark, could barely hear the idling engine above the soft sound of the breeze and the splash of water against the bow. He had the sensation of gliding on a sailboat, and he was gratified that they were in deep enough water that he would not have to worry about reefs for awhile....

"Ship at two o'clock!" Marney shouted to Kennedy from the gun turret.

Kennedy glanced obliquely off his starboard bow. Ross was already pointing up to a shape suddenly sculptured out of the darkness behind a phosphorescent bow wave.... For a few unregainable moments Kennedy thought it was one of the scattered PT boats. So did Mauer. So also did some of the crews of PT 162 and PT 169, who sighted the Amagiri at about the same time or perhaps seconds earlier. As the shape grew, Kennedy and Mauer quickly recognized that it was not a PT boat. On PT 169 Potter called a warning on the radio, but it either was not received aboard 109 or else arrived too late. "Lenny", Kennedy said in a matter-of-fact voice, "look at this". Ensign Thom stood up. What followed took place within the span of perhaps forty seconds or less.... On the foredeck of PT 109 Ross frantically grabbed a shell and rammed it at the 37-millimeter. It slammed against a closed breech. He knew he would never have time to load.... "Sound general quarters", Kennedy told Maquire.... Back in the cockpit...Kennedy spun his wheel in an instinctive attempt to make a torpedo attack on the Amagiri. The torpedoes, however, would not have exploded even if they had struck the destroyer, because they were not set to fire at such a short distance. Moreover, PT 109, idling on a single engine, was moving so sluggishly that there was no chance to maneuver against the swiftness of the destroyer.... The steel prow of the Amagiri crashed at a sharp angle into the starboard side of PT 109 beside the cockpit....

The wheel was torn out of Kennedy's grasp as he was hurled against the rear wall of the cockpit, his once-sprained back slamming against a steel reinforcing brace.... The destroyer, smashing through the gun turret, sliced diagonally behind the cockpit only several feet from the prostrate skipper. Helplessly looking up, Kennedy could see the monstrous hull sweeping past him through his boat, splintering her and cleaving the forepart away from the starboard side of the stern. In the engine room McMahon had had no warning of danger. He was standing among the engines, casually touching the manifolds to make sure they were not gettng too hot and regulating the scoop controls, which fed sea water through the cooling system.... Something on one of the guages caught his attention, and he was climbing over machinery to look at it when a tremendous jolt flung him sideways against the starboard bulkhead and toppled him into a sitting position alongside an auxiliary generator. In disbelief he saw a river of red fire cascading into the engine from from the day room.... The river of fire rose about him. It seared his hands and face and scorched his shins, exposed by his rolled-up dungarees. He held his breath to keep the flames from his lungs. He was fairly engulfed in a world of blinding light and roasting heat and then without any transition he was immersed in a watery darkness, his lungs almost bursting. Sheared away by the destroyer, the flaming stern was pulled down by the weight of the engines... Bobbing to the top in his kapok, he emerged in a sea of fire.

The burning gasoline was spreading across the water in a garish patch of light that could be seen by Lt Evans on his hilltop a few miles away. He knew that a ship must be on fire, and he supposed he might hear more about in in time....

During the long hours of darkness most of the men had climbed up on the hulk and reclined with their feet braced against some fixture to keep them from sliding off the deck. They spoke in low voices about the prospects of rescue after daylight. Some thought PTs would return for them; others guessed that a PBY would pick them up.

When dawn broke over Wana Wana they could see Rendova Peak thirty-eight miles to the south. They knew almost exactly where they were. They knew that the other boats would be back at the base now, that Lumberi would be stirring with the morning's activity and that their absence would set in motion a search that should lead speedily to their rescue. There was already some cause for this optimism.

Sweeping Blacket Strait with his binoculars in the early light, coastwatcher Evans saw an object floating near where he had observed the blaze during the night. In his morning report to New Georgia and Guadalcanal, which had the call letters KEN (after Lt Commanderr Hugh McKenzie, one of the great coastwatchers, who, from his headquarters in Guadalcanal, commanded the organization's activities in the Solomons), Evans noted:

...ALL FOUR [destroyers] WENT WEST OWE TWO TWO OWE X

PLANE DROPPED BOMBS NEAR SAMBIA AND LATER NEAR GATERE X

SMALL VESSEL POSSIBLY BARGE AFIRE OFF GATERE AND STILL VISIBLE

At 9:30 AM, upon receiving notification from the PT base, the coastwatcher near Munda (call letters PWD) informed Evans:

PT BOAT ONE OWE NINE LOST IN ACTION IN BLACKETT STRAIT

TWO MILES SW MERESU COVE X CREW OF TWELVE X

[s/b 13; Ross name not on crew list]

REQUEST ANY INFORMATION

Aboard PT 109 in the meanwhile day light had substituted the dread of exposure for the terror of darkness. While inflating hopes for rescue, the sunrise had also torn away the protection of night. Rendova Peak was a comforting sight, but it rose far beyond the confines of Blackett Strait. The eleven Americans were encircled by Japanese. They could see buildings on Kilombangara and Gizo.... So far as Kennedy and the men knew the enemy might already be preparing to come out after them. "What do you want to do, fight or surrender?" Kennedy asked his crew. "Fight with what?" someone asked. They took stock of their weapons.... To lessen their chances of being seen Kennedy slid into the water along the port side and ordered everyone in after him except Johnston and McMahon. He again brought up the question of what should be done if the Japanese came out. "There's nothing in the book about a situation like this:", he said. "A lot of you men have families and some of you have children. What do you want to do? I have nothing to lose". This struck Maquire as incongruous. He felt that because of his wealth and advantages Kennedy had the most to lose. No one favored surrender, because of the tales they now recalled about Japanese torture of prisoners, but some of them questioned whether it would be possible to put up a fight. No one knew for sure whether their sidearms would fire after so many hours in the water. There was no way to dry them.... Zinser also suggested that they make no definite decision until they saw the size of any Japanese force that might come after them. No one had any better suggestions, and this was the way the matter was left.

By 10am the list to starboard had become so acute that the bow turned turtle but remained afloat. The men helped McMahon and Johnston onto the upturned bottom.

At 11:15am Evans messaged PWD, Munda:

REF YOUR 0930/2 NO SURVIVORS SO FAR X

OBJECT STILL FLOATING BETWEEN MERESU AND GIZO X

THREE TORPEDOES AT VANGAVANGA

When the bow turned turtle Kennedy knew that something would have to be done if they were not rescued soon. The hull seemed to be settling in the water. If it should sink that night with them still hanging on, they would become separated in the dark, and some would surely drown. On the other hand, if the bow stayed afloat and drifted with the men clinging to it, they would be at the mercy of the currents. For all Kennedy knew they would drift right into the arms of the Japanese. It became increasingly evident that if help did not come within a few hours, he would have to order the men to abandon the boat and swim to shore before dark....

Now and then he and his men sighted a plane in the distance. In hope that it was an Allied aircraft they would wave, but the plane would drone on, and Kennedy would order them to stop waving lest they attract the enemy.

The men cursed war, they cursed the Navy, they cursed Lumberi, they cursed the PT boats that should have been thundering to their rescue and the planes that should have been circling reassuringly overhead.... The problem of sharks was mentioned casually. Several times since daybreak the men had seen porpoises. Since sharks are thought to stay clear of the leaping, playful porpoises, the sight eased the sailors' minds for the time being.

At 1:12pm Evans received a message from KEN, Guadalcanal:

DEFINITE REPORT PT DESTROYED LAST NIGHT BLACKETT STS

APPROX BETWEEN VANGA VANGA AND GROUP OF ISLANDS SE OF GIZO X

WAS SEEN BURNING AT ONE AM THE CREW NUMBERS TWELVE

[s/b 13; Ross name not on crew list]

POSSIBILITY OF SOME SURVIVORS LANDING

EITHER VANGAVANGA OR ISLANDS

...Sometime after one o'clock Kennedy said that they would have to abandon PT 109 and try to get up on land somewhere before dark. He told them that they would head for the island group east of Gizo. There was considerable discussion about which of these islands it would be best to go to. No one relished the risk of swimming ashore, but they agreed that the worst hazard would be staying with the boat too long. Every hour increased the danger of detection. From the position to which they had drifted since the collision Naru was nearer than any of the other islands. On the other hand, Naru appeared large enough to Kennedy to have a Japanese outpost, particularly since it looked out directly on Ferguson Passage. He pointed to Plum Pudding Island, so named because of its shape, and said that even though it was somewhat farther away, it was smaller and less likely to contain Japanese than Naru [sometimes called Cross; sometimes spelled Nauru; sometimes spelled Gross]. No matter which he chose it would be a gamble. He decided that they would strike out for Plum Pudding.

Since some of the men were better swimmers than others, Kennedy knew it would be difficult to keep the group together on the long swim. Furthermore McMahon, whose burns were dreadful to look at, was helpless. In getting ready to shove off Kennedy noticed that one of the two-by-eight planks they had placed under the 37-millimeter in Rendova Harbor the day before was still floating by the bow at the end of its rope. This plank, he thought, might solve the problem of separation.

"I'll take McMahon with me", he said. "The rest of you can swim together on this plank. Thom will be in charge.

The men who still had shoes removed them and tied them around the plank. They took the boat's battle lantern, a ten-pound, square gray flashlight, wrapped it in a kapok to keep it afloat and tied the kapok to the plank also.... "Will we ever get out of this?" someone asked. "It can be done", Kennedy told him. "We'll do it".

With a last look at PT 109 they cut the two-by-eight loose from the bow and, buoyed by their kapoks, grouped themselves around the plank, four on one side and four on the other, with a ninth man, often Thom, going back and forth from one end to the other, pushing and pulling at the plank. The men on the sides each threw an arm over the plank and paddled with the other. All of them kicked.... The kicking would not only hasten their crossing but would tend to scare sharks away.... They still felt they must have been observed. They wondered when the Japanese would come after them. There was no way of putting up a fight now.

McMahon, sure that death was only a matter of time, remained silent when Kennedy helped him into the water, which stung his burns cruelly. In the back of his kapok a three-foot-long strap ran from the top to a buckle near the bottom. Kennedy swam around behind him and tried to unbuckle it, but the strap had grown so stiff from immersion that it wouldn't slide through. McMahon was surprised at the matter-of-fact way Kennedy went about it all. It was as if he did this sort of thing every day. After tugging the strap a few times Kennedy took out his knife and cut it. Then he clamped the loose end in his teeth and began swimming the breast stroke. He and McMahon were back to back. Kennedy was low in the water under McMahon, who was floating along on his back with his head behind Kennedy's.

At the start the eleven survivors were all close together, but gradually Kennedy pulled ahead with McMahon in tow. Kennedy had swum the backstroke on the Harvard swimming team and was generally a strong swimmer.

Towing McMahon he would move in spurts, swimming the breast stroke vigorously for ten or fifteen minutes and then pausing to rest. "How far do we have to go now?" McMahon would inquire. Kennedy would assure him that they were making good progress. "How do you feel, Mac?" he would ask, and McMahon would invariably reply, "I'm okay, Mr Kennedy, how about you?" Being a sensitive person, McMahon would have found the swim unbearable if he had realized that Kennedy was hauling him through three miles or so of water with a bad back. He was miserable enough without knowing it. Floating on his back with his burned hands trailing at his sides, McMahon could see little but the sky and the flattened cone of Kolombangara. He could not see the other men, though while all of them were still together, he could hear them puffing and splashing. He could not see Kennedy but he could feel the tugs forward with each stretch of Kennedy's shoulder muscles and could hear his labored breathing. McMahon tried kicking now and then but he was extremely weary. The swim seemed endless, and he doubted that it would lead to salvation. He was hungry and thirsty and fearful that they would be attacked by sharks. The awareness that he could do nothing to save himself from the currents, the sharks or the enemy oppressed him. His fate, he well knew, was at the end of a strap in Kennedy's teeth. At that stage of his life it never occured to him to pray. His sole reliance was on Kennedy's strength....

From Kolombangara at 4:45pm Evans messaged KEN:

THIS COAST BEING SEARCHED X

IF ANY LANDED OTHER SIDE WILL BE PICKED UP BY GIZO SCOUTS X

OBJECT NOW DRIFTING TOWARDS NUSATUPI IS

Evans told the native scouts to pass the word among the islands to be on the lookout for PT boat survivors....

Near sundown on Monday, August 2 Kennedy and Pat McMahon half drifted up on the southweastern rim of Plum Pudding Island. Reaching the clean white sand seemed to be the ultimate limit of Kennedy's endurance. His aching jaws released the strap of McMahon's kapok, the end of which was pocked with Kennedy's tooth marks. For a time Kennedy lay panting, his feet in the water and his face on the sand. He would have been completely at the mercy of a single enemy soldier, but the island was deserted. His feet blistered, McMahon crawled out of the water on his knees and feebly helped Kennedy up. Swimming with the strap in his teeth Kennedy had swallowed quantities of salt water. When he stood he vomited until he fell again in exhaustion. McMahon's hands were swollen grotesquely. Every move he made tortured him. He knew, however, that as long as they were on the beach they would be exposed to view. He tried to drag Kennedy across the ten feet of sand, yet he could scarcely drag himself. He found he could crawl, and as Kennedy's strength returned he too crawled across the beach in stages with McMahon until the two of them collapsed under the bushes. After awhile Kennedy was strong enough to sit up and watch the others as they neared the beach on their two-by-eight plank....

It took the eleven survivors fully four hours to swim the three and a half miles across Blackett Strait from the overturned hull of PT 109 to Plum Pudding Island.... As they approached the island finally, Kennedy waved to them from under the trees. When they saw him they felt the relief of men who had come safely through the first round of danger.... The nastiest part was getting through the coral.... When they finally dragged the plank up on the beach they looked every inch the part of nine shipwrecked sailors. The men ducked under the trees near Kennedy and McMahon....

Suddenly the men were frozen by the sound of a boat approaching from the direction of Ferguson Passage.... A motorized Japanese barge with three or four men in it was chugging up Blackett Strait only a couple of hundred yards away.... The barge moved slowly, but it did not turn.... If the Japanese had come by only a few minutes earlier they would have caught Kennedy and his men helpless in the water. They could have shot or seized them, as they pleased. Although the barge passed, the sight of it frightened the men deeply. How many more barges would pass? Where else might the Japanese be? For all the men knew there were some on the same island with them, and they did not dare to venture more than a short distance from the clump of bushes and the beach. They spoke in hushed tones....

From his knob five or six miles directly across from them Lt Evans was getting off his last message of the day. Having seen a flight of Allied planes and assuming they were looking for the survivors, he asked KEN:

WILL YOU PLEASE ADVISE RESULT OF SEARCH BY P FORTYS OVER GIZO

He received no answer that night...

On Plum Pudding Island the men were obsessed with thoughts of food (they had none) and of rescue. This was all everyone talked about as the sun went down. It never occurred to them that they had been all but given up for lost by their comrades.... The three officers, Kennedy, Thom, and Ross, drew aside and conferred among themselves. The question was simply put by Kennedy, "How are we going to get out of here?" As they hashed over the problem, their theory of rescue boiled down almost exclusively to the idea of intercepting the PT boats in Ferguson Passage, difficult through it would be for a swimmer to attract their attention in the dark.

Quietly Kennedy said that he would swim out into the passage that night and see what he could do with his revolver and the battle lantern.... "If I find a boat", he said, "I'll flash the lantern twice".... He stripped down to his skivvies and strapped the rubber life belt around his waist. He wore shoes to protect his feet on the reefs. He hung the .38 from a lanyard around his neck. The revolver swung at his waist, the muzzle pointing down. He wrapped the battle lantern in kapok to float it. Dusk had settled over Blackett Strait when he stepped into the water.... Before long Kennedy was a speck disappearing in the water....

The line of the reef bends southward from Plum Pudding along the line of the anchor, past Three Palm Islet to Leorava, the sandbar next to Naru. Thence, curling around into the outer arm of the anchor, it forms the upper boundary of Ferguson Passage. Kennedy's objective was to follow the reef until it touches Ferguson Passage and then to leave it and swim out into the passage. The depth of the water along the way varies. Sometimes Kennedy could walk in water waist-deep or shoulder-deep. At other times the reef would fall away and he would have to swim until his foot touched it again. Now and then he would lie on the water and grasp coral outcroppings and pull himself along to spare his legs. As darkness came on it was an eery trek. Often when he put his foot down something darted away in the water. He could tell that the reef was alive with creatures strange to him.

Once he saw a huge fish and winced at the recollection of tales he had heard of the mutilation of men by sharks and barracuda. He flashed his light and thrashed his arms and legs. The fish swam away. The coral bottom was slippery. Occasionally Kennedy would slip against a fascicle of coral and cut his leg. At other times he would step unwittingly into a deep hole and go under. After nightfall Blackett Strait was lonelier than a desert. As landmarks disappeared, Kennedy's sense of direction blurred.... His only map was the reef.... Though the water was warm, Kennedy would often feel cold.... Stumbling, slipping, swimming along Kennedy finally reached Ferguson Passage after having traveled a distance of between two and three miles.

Pausing to rest, he took off his shoes and tied them to his life belt. Then he floated off the reef and struck out for the center of Ferguson Passage, towing the battle lantern along in the kapok.... Out in Ferguson Passage he treaded water, looking toward the Solomon Sea and listening.... Instead of PT boats, Kennedy saw only aerial flares beyond Gizo.... What he did not know was that Warfield had dispatched the boats to the southern tip of Vella Lavella. They would be operating that night not in Ferguson Passage but in Gizo Strait miles to the north. As hours passed and no boats appeared Kennedy concluded that they had gone up west of Gizo and were operating in Gizo Strait.....

Foggy and tired from his long hours in the water, Kennedy faced back toward the reefs and started swimming again. His limbs were lifeless. To lighten his burden he untied his shoes from the lifebelt and let them sink.... He moved on and on through the darkness but he never seemed to come to the reef.... A current through Ferguson Passage was carrying him sideways into Blackett Strait....

When daylight came the discovery Kennedy made with his weary wits was that in spite of a debilitating expenditure of energy he was still wallowing about at the confluence of Ferguson Passage and Blackett Strait. As dawn spread a pale light on the water, he was able to reorient himself. He had just enough strength to make it back to Leorava, the tiny islet with one tree and a patch of bushes. Crawling up on the sands, he collapsed in a deep slumber....

During the long dark hours that Kennedy had been swimming through the wastes of Ferguson Passage the Japanese had landed from two to three hundred more soldiers at Kequlavata Bay on the northern coast of Gizo Island. Some of the Gizo Scouts -- the natives who were working for Lt Evans -- had a camp at Sepo Island, between Plum Pudding and the site of the landing, and they spotted the Japanese reinforcements. They knew that they must carry this intelligence to the coastwatcher.

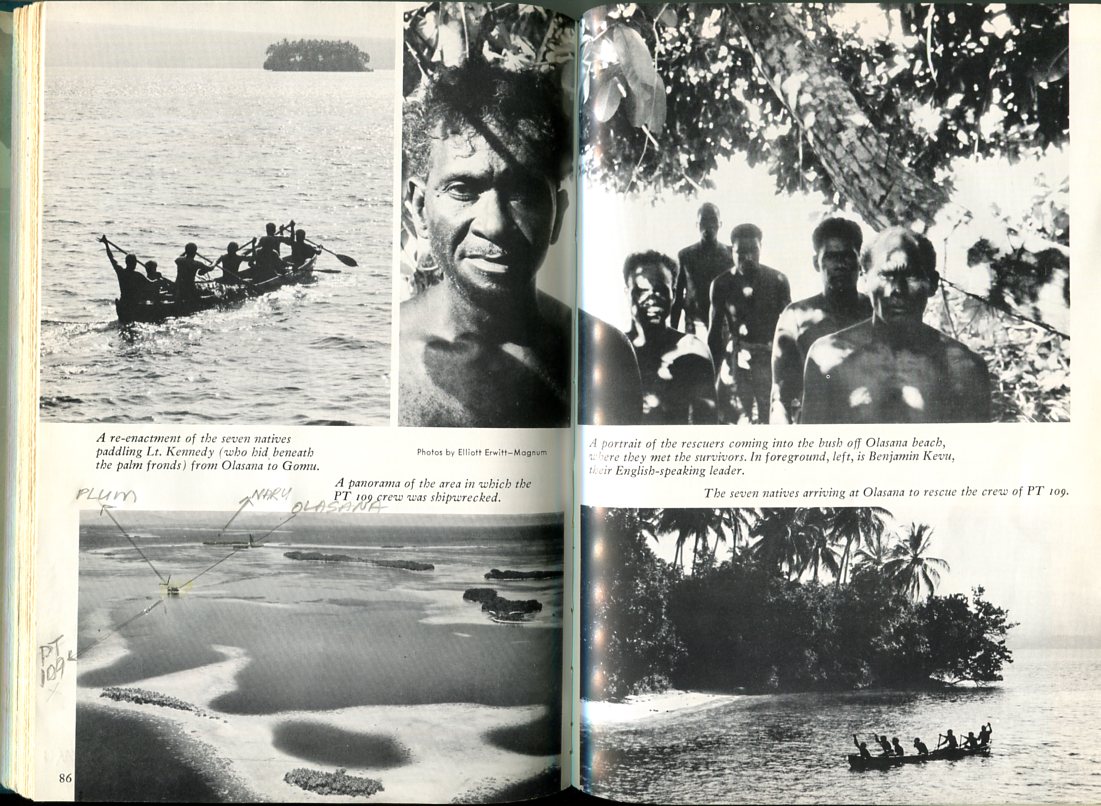

Early on the morning of Tuesday, August 3, therefore, Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana climbed into a dugout canoe and paddled down Blackett Strait on a mission as simple as any in the greatest of all wars culd possibly be. Yet by a most extraordinary combination of circumstances this mission was destined to result in the saving of eleven officers and men of the United States Navy, one of whom would become the President of the United States with the lifetime of Biuku and Eroni.

Biuku and Eroni were ebony-colored Melanesians of slight stature but superb form. Eroni's face wore a stern, intense expression, while Biuku looked blithe and gentle. Both youths were around nineteen. Biuku had been born on Wana Wana Island and briefly attended a Methodist mission school run by the Australians. Religion affected him. Although he understood little English, he could say, "In God we trust" with more meaning than the phrase carries on most lips. Eroni was born in Lake Village on Ganongga Island and also had received instructions before the war in a Methodist school. Like Biuku, he was loyal to the British and was willing to help Britain's allies when war burst into the Solomon Islands.

The two young natives paddled for a long time without seeing anything unusual except some flotsam off Bambanga Island. They fished out of the water a box that contained a razor, a shaving brush, a tube of shaving cream and a handwritten letter, which they could not read. They carried the letter with them. In a brief pause at Wana Wana they showed it to Benjamin Kevu, an older scout, who read and spoke English well, having been an employee of the British post office at Gizo before the Japanese invasion. Benjamin observed that the letter was signed by Raymond Albert [survivor from PT 109]. He had no idea who Albert was or where he had come from, and the letter meant nothing to him. From Wana Wana, Biuku and Eroni moved on by canoe to report to Lt Evans on Kolombangara.

Tuesday, August 3, was to be a busy day for Evans. After an overnight wait for his inquiry about the findings of the P-40s over Gizo, he was first informed that the planes had not been on a search but were merely passing by on an unrelated mission. Later PWD, New Georgia, corrected this in a message to Evans, referring to him by his call letters:

AIRINTEL HERE HAVE REQUESTED US TO TELL GSE

A SEARCH WAS MADE YESTERDAY DUSK WITH NEGATIVE RESULT

The failure of the planes to locate survivors compounded the problem. If an air search could not locate the missing men, what justification did Warfield have at this stage of the campaign for risking boats in enemy waters looking for them? Ensign Battle had wanted to go back up into Blackett Strait during the day on August 2 in PT 171. He might well have found the eleven survivors while they were still clinging to the hulk of PT 109. Under the circumstances, however, he was denied permission. If Evans could see the floating bow, which, presumably, is what he saw, how could planes fail to spot eleven men on a clear day in a body of water only about five and a half miles wide at that point? The explanation evidently lies in the report of Air Intelligence that the search was made at dusk. In other words, in the endless confusion surrounding this event, the search was delayed so long that by the time the planes reached the Gizo area the survivors were hidden under the trees on Plum Pudding Island.

Evans had no better word for his base than his base had for him. He messaged KEN:

SEARCH NEGATIVE

EXCEPT ONE MORE TORPEDO AT PILPILI

As Biuku and Eroni were on their way to Kolombangara Kennedy woke up in broad daylight on the tiny island Leorava. He felt cold and utterly ragged and still had a mile and three-quarters to swim to return to his men. He tried the battle lantern but it did not light, so he tossed it aside. His shoes having been discarded the night before, he waded back into the water in his skivvies with only his lifebelt and revolver. The coral cut his bare feet as he started back up the reef.

...On Plum Pudding as the men were lying in the bushes late in the morning idly watching the gulls fish in Blackett Strait, Maquire suddenly saw...Kennedy swimming in from the reef.... Kennedy fell to the beach, retching. He looked skinny, bedraggled and exhausted. He had a beard. His hair was matted over his forehead. His circled eyes were bloodshot. His sun tan had taken on a yellowish hue. Thom and Ross dragged him across the sand into the bushes. When Maquire asked him how he felt, he grunted. After awhile someone inquired whether he had seen any PT boats. "No", he said. He muttered something about being unable to control his movement in the currents. He became very sick and then fell asleep. The others could think of nothing to do. They sat there as the afternoon wore on. Once Kennedy woke, looked up at Ross and said, "Barney, you try it tonight", and then went back to sleep.

Ross was convinced of the futility of swimming into Ferguson Passage, but he obeyed. Warned by Kennedy's ordeal, he set out at four o'clock in order to reach the pasage while it was still daylight. He was afraid he would get lost among the islands. He told the others not to expect him that night unless he succeeded in signaling a boat. If his mission should prove unfruitful, he would remain on one of the reef islands until daylight.... He took Kennedy's Smith & Wesson on the lanyard. Also, to reduce the risk of attracting sharks by the white shade of his legs he donned khaki pants. As he slithered and swam along the reef, he was appalled to see some sand sharks three or four feet long.

When Ross reached Ferguson Passage dusk was falling. Soon it was not only lonely and silent but pitch-dark.... Since it was still too early to go out, he swam about until his foot touched a coral head where he could stand in chest-deep water outside the reef...until he guessed it was time for the PT boats to approach.... He swam out into Ferguson Passage for about twenty minutes.... He treaded water and waited. He did not know...that the PT boats had again gone up to Vella Lavella. He hauled the .38 out of the water and pulled the trigger. The revolver fired, but the shot sounded flat against the broad surface of the water. At intervals he fired twice more. After a long wait he swam back to the reefs and was happy to discover that he had come in near an islet, which was Leorava, Kennedy's resting place the night before. He went ashore and promptly fell asleep.

On the morning of Wednesday, August 4, Ross awoke in the warm sun feeling fine.... By the time he started swimming back to Plum Pudding, Biuku and Eroni had reached Evan's hilltop with the news of the Japanese landing at Kequlavata Bay. Evans asked them if they had seen or heard of any PT boat survivors in the islands around Gizo. They said they had not, whereupon the coastwatcher at 10:25am messaged PWD:

NO SURVIVORS FOUND AT GIZO

As they left to return to Sepo Island, the native scouts were reminded by Evans that there might be PT survivors in the Gizo area. At 11:30am Evans received a message from KEN:

WHERE WAS HULK OF BURNING PT BOAT LAST SEEN X

IF STILL FLOATING REQUEST COMPLETE DESTRUCTION X

ALSO REQUEST INFORMATION IF ANY JAPS WERE ON OR NEAR FLOATING HULK

Because of other traffic Evans did not reply until 5:05pm when he messaged KEN:

CANNOT CONFIRM OBJECT SEEN WAS FLOATING HULK OF PT X

OBJECT LAST SEEN APPROX TWO MILES NE BAMBANGA DRIFTING SOUTH X

NOT SEEN SINCE PM SECOND X P FORTYS FLEW OVER IT AND

GIZO SCOUTS HAVE NO KNOWLEDGE OBJECT OR ANY JAPS THAT VICINITY

...After Ross's return to Plum Pudding Kennedy decided that they would move to Olasana Island, situated close to the bottom of the anchor shaft and only one island removed from the passage. Olasana lies a mile and three-quarters inward from Plum Pudding in a southwesterly direction. Again the men dragged the plank into the water, and once more Kennedy took the strap of McMahon's kapok in his teeth and towed him. Kennedy was running the risk of leaving a safe island for one occupied by Japanese. They had not noticed any activity around Olasana, however, and they could see that it abounded in coconut palms....

The eleven survivors gathered in the trees behind the curved beach on the southeastern tip of Olasana, whence they could look straight across another half-mile of water to Naru Island bordering Ferguson Passage.... By dark all were weary from the long swim. For the first time in three nights no one went into Ferguson Passage. For the first time in three nights the boats came through Ferguson Passage and were on station in Blackett Strait by 9:30pm....

Thursday, August 5 dawned bleakly for the castaways on Olasana Island. This was the fourth day of their ordeal. The longer they remained in these islands the greater was the danger they would be found by the Japanese....

If PT 109 was only a sad memory for its crew, it was still a preoccupation of Lt Evans and his coastwatcher associates. At 9:40am he messaged KEN:

SIMILAR OBJECT NOW IN FERGUSON PASSAGE DRIFTING SOUTH X

POSITION HALF MILE SE GROSS IS X

CANNOT BE INVESTIGATED FROM HERE FOR AT LEAST TWENTY-FOUR HOURS

A couple of hours later he informed KEN:

NOW CERTAIN OBJECT IS FOREPART OF SMALL VESSEL X

NOW ON REEF SOUTH GROSS IS

And still later:

HULK STILL ON REEF BUT EXPECT WILL MOVE WITH TONIGHTS TIDE X

DESTRUCTION FROM THIS END NOW MOST UNLIKELY X

IN PRESENT POSITION NO CANOES COULD APPROACH THROUGH SURF

On Olasana Kennedy went down the beach a short distance from the men and beckoned Thom and Ross.... He looked across to Naru Island. It was only a half-mile swim. The far side of it faced Ferguson Passage, but what of that? No Allied vessels would be operating there in daylight. Kennedy had no scheme into which a visit to Naru fitted. But more or less on the spur of the moment he said to Ross, "Let's take a look at this one anyway".

At practically the same time Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana got into their canoe on Wana Wana Island to cross Ferguson Passsage and head back up Blackett Strait to return to their station on Sepo Island. After making their report to Evans the previous day, they had left Kolombangara and passed the night at the native village of Raramana on Wana Wana. Now, after taking leave of friends there, they started paddling on the most direct route to Sepo, which would take them close by Naru, opposite Ferguson Passage from Raramana.

Compared with their earlier swims Kennedy and Ross found the crossing to Naru easy. It was shortly after noon when they crawled up on the white beach of the narrow, four-hundred-yard-long island at the base of the anchor.... The distance across the island is short, and they reached the Ferguson shore quickly. Looking out from the fringe of trees, they could see Rendova Peak in its full outline. It was still nearly thirty-eight miles away, but across open water and low islands it looked exasperatingly accessible. Certainly there must be some way, they thought, for eleven men to get to it. They started along the beach to their left. On the reef about a mile or so from the shore they spied the wreckage of a small Japanese vessel, which is probably what the P-40s had been strafing, and a short distance farther they came upon what appeared to be cargo washed ashore.... They ripped open a rope-bound crate, which to their delight contained hard candy in the shape of tear drops.... They had barely gone another twenty yards when they found a dugout canoe that someone had left in the bushes with a large tin of rainwater. Without knowing it they had come upon one of the caches the native scouts had scattered among the islands. They sat down by the canoe and sparingly drank some of the water.

As Biuku and Eroni neared the Naru side of Ferguson Passage they too noticed the Japanese wreckage on the reef and decided to see whether it contained anything of interest. Reaching the reef they anchored their canoe a short distance away and climbed into the hulk. While Kennedy and Ross were quenching their thirst with a can of rainwater, Biuku and Eroni were satisfying their own curiosity by poking through the gear, charts and and utensils of one sort and another that were strewn about the deck. The only booty that interested them was Japanese rifles. They each took one and stepped back down on the reef just as Kennedy and Ross re-emerged on the beach.

Across a mile of water both pairs of men instantly spotted one another. Eroni and Biuku, terrified that the two on the beach were Japanese stranded by the wreck and might shoot them, splashed along the reef and tumbled into the canoe, Eroni in his haste dropping his rifle. Kennedy and Ross, thoroughly alarmed that they had been sighted at last by the Japanese, dived into the bushes. Who were these men? Had they actually seen Kennedy and Ross? Would the Japanese garrison soon be alerted to search the islands? The trip to Naru that had begun so auspiciously was now filled with dismaying possibilities.

Eroni and Biuku paddled furiously away from Naru toward Blackett Strait. Once they had rounded the sandbar of Leorava they were headed in the direction of Sepo Island and away from the eleven Americans. If they had just kept going, they would have reached their headquarters several miles away and perhaps forgotten all about the two figures on Naru. At that moment their only interest in the two men was to get away from them and their only mission was to return to Sepo. Had they kept going as they were for just a short distance farther, eleven men on a small Pacific island might never have been heard from again. But at the last moment, they veered clear off their course and headed for Olasana Island. Biuku had become thirsty from the exertions of their sprint from Naru and persuaded Eroni, who was paddling in the stern, to turn in to Olasana for coconuts. So they took a sharp turn to the left and paddled for the closest point of Olasana, which was the beach at the southeastern tip of the island.

When Kennedy had departed for Naru with Ross he left Thom in charge of the other men. All nine were resting in the bushes behind the beach waiting to hear what the skipper had found on the other island when almost simultaneously three or four of them saw the canoe approaching with the two natives.... These strangers looked like boys. Perhaps they were scouts for the Japanese on Gizo. If not, there was still no basis on which the men could safely assume that the natives would be friendly.... At this point, however, Thom made a fateful decision. In a gamble that involved all their lives he stood up and walked out on the beach in sight of the strangers, who were now within thirty feet of the shore.

The sudden apparition of the tattered and bedraggled giant with the blond beard astounded Biuku and Eroni. Nothing in their experience had prepared them for the sight of such a man. In sheer fright they back-paddled as fast as their arms would go. Thom ran out to the water's edge and beckoned them with his right hand. "Come, come", he called. Fearful again that they had happened upon Japanese, the natives turned their canoe about, thereby bringing a crisis for the Americans. Self-preservation itself might demand that these men be stopped with bullets if necessary, from going off and possibly reporting their presence to the Japanese. But if the bullets failed to halt them, the very act of firing would arouse their hositility and might provoke them into reporting them. And, either way, the flight of the natives might end the only chance of rescue. "Navy, Navy", Thom pleaded. "Americans, Americans".

Eroni and Biuku were a sufficiently safe distance away to pause and listen. The trouble was they didn't understand what Thom was saying. Sensing their doubts, he said, "Me no Jap" and rolled up his right sleeve and showed them his white skin. Biuku and Eroni still remained dubious. Thom tried another tack. "Me know Johnny Kari", he said. John Kari was the headman at Wana Wana, who was known to the PT men through his visits to Lumberi as a native scout. Still no response from Biuku and Eroni. Then Thom got an inspiration.

"White star", he said, pointing to the sky, "White star". At last Biuku and Eroni understood. Now they were reassured that Thom and the men who were emerging from behind the trees behind him were allies. Slowly the two natives paddled ashore. The insigne on American aircraft was a white star set in a white bar. The coastwatchers instructed their native scouts that airmen who crashed or parachuted from planes bearing the white star were to be treated well and brought with all possible haste to a coastwatcher's station.

The survivors helped Biuku and Eroni drag their canoe across the narrow beach and conceal it between two palm trees. When they all gathered together in the bushes, the meeting was awkard, because the natives were uncomprehending and shy, and few of the sailors really trusted them. Little by little the Americans learned to communicate with Biuku and Eroni. When they understood what the two were trying to say there were shocked. The natives -- thinking of Kennedy and Ross -- pointed to Naru and indicated the island contained Japanese. This filled the men with grim doubts as to whether they would ever see the two officers again....

On Naru, after a long and apprehensive wait in the bushes, Kennedy and Ross, seeing no further signs of the two men in the canoe, resumed their exploration of the island without making any more discoveries. With the canoe that they had found in the bushes earlier Kennedy now felt much more mobile. He decided to venture out into Ferguson Passage that night, believing he would have a better chance of intercepting the PT boats in a canoe than if he were swimming. While it was still light, however, he wanted to take the candy and water back to the men on Olasana. He tore a slat off the crate for a paddle and suggested that Ross wait for him. When he left, Ross fell asleep on the beach....

That afternoon Evans messaged KEN:

ANTICIPATE MOVING TOMORROW X FINAL ADVICE AM

Evans had come to the conclusion that from Kolombangara he was not getting a good enough view of things in Ferguson Passage and the west side of Blackett Strait. He needed to be more in the center of the area. He passed the word among his scouts, therefore, that the next day he planned to move to a new station on Gomu, one of several smaller islands north of Wana Wana in lower Blackett Strait about seven miles east of Naru, or, as it was also know to evans, Gross Island. That same afternoon of Thursday, August 5 he received an advisory from PWD:

AIRINTEL ADVISE THAT HULK WAS EXAMINED BY PLANE TODAY AND

WAS THAT BADLY DAMAGED THAT IT WAS NOT WORTH WASTING AMMUNITION

This was the last that was ever known of PT 109.

Kennedy arrived back on Olasana from Naru, to the inexpressible relief of the men. He was surprised to find the two natives, not realizing, of course, that these were the same two men he and Ross had seen. And he was at a loss to know why Biuku and Eroni should be so certain that there were Japanese on Naru. The only thing Japanese he had found on the island was wreckage and candy, and proceeded to distribute the candy among the nine ravenous men. He also took the tin of water out of the canoe and left it with them before rejoining Ross for the paddle into Ferguson Passage. Kennedy's hopes would have been high indeed if he could have known that Warfield had ordered the boats through Ferguson Passage that night to patrol in Blackett Strait.

On Naru, however, Kennedy and Ross were in difficulty. The waves were now smashing over the reef, and the wind was rising. Ross thought it foolhardy to pit a canoe against such weather at night and said so..... Once beyond the reef the sea ran too high for them. With slats for paddles they could not keep the bow in to the waves. Water splashed over the gunwales. In the stern Ross tried bailing with a coconut shell, but more water poured into the canoe. As they were shouting to each other about turning back a five-foot wave capsized them.... They splashed about in the dark unntil they got a grip on the overturned canoe which had survived the crash intact.... On lacerated feet Kennedy and Ross made their way ashore on Naru. When they reached the beach they lay down in exhaustion.... "This would be a great time to say I told you so", quipped Barney, "but I won't"....

The PT boats rolled through the heavy sea and were on station in Blackett Strait at 9:15pm....

On Friday, August 6, a new animation and earnestness crept into the affairs of the Americans.... Kennedy on Naru and his men on Olasana were beginning to feel strongly that they could now do something to help themselves. They had two canoes, and the natives were still with them, having remained overnight on Olasana and built them a fire by rubbing sticks together. Some of the men, as mistrustful as ever, had only pretended to sleep when Biuku and Eroni turned in with them. All night long they had kept a suspicious watch over the natives....

Despite the battering in Ferguson Passage the night before, Kennedy had been up early and paddled back to his men on Olasana before Ross awoke. When Ross sat up in the sand he was not surprised to find him gone. Kennedy was always on the move, always going somewhere. With his deep-set eyes and black beard Barney Ross looked like Abe Lincoln in Melanesia. All things considered, he was not feeling badly. He was worried, but for five days fear had been a constant companion, and he had learned to live with it. He swam over to join the others on Olasana and they all sat around talking about how they could best put the canoes and the natives to their service. Kennedy and Thom did not share the suspiciouns of the men. They were confident that the natives could be trusted.

While they were talking, Lt Evans at 11:10am radioed KEN:

CLOSING DOWN AT TWO PM

AND WILL COMMUNICATE EARLY TOMORROW

With that Evans gathered his weapons and gear from his hut and trekked down the hillside on Kolombangara with some natives to wait at the shore until dusk when he would paddle to Gomu.

Still without a definite plan of action, Kennedy persuaded Biuku and Eroni by animated sign language to paddle him back to Naru for another look at Ferguson Passage. Unable to communicate in any but the most rudimentary way with his new ally, Kennedy knew nothing about Evans. As he looked across the passage and the distant flat islands and saw Rendova Peak, he decided that the only practical way to get help would be to send Biuku and Eroni all the way to Lumberi with a message. He pointed to Rendova Peak and said, "Rendova, Rendova". Biuku and Eroni nodded. "Come here", Kennedy said and led Biuku back into a clearing roofed by towering palms. Kennedy picked up a coconut and had Biuku quarter it. By sticking a sharpened peg in the ground and splitting a coconut on it, the natives know how to husk a coconut in about a tenth of time it takes an inexperienced white man. Kennedy took his sheath knife and on a polished quarter of the coconut he inscribed the following message to the PT base commander:

NAURO ISL

NATIVE KNOWS POSIT HE CAN PILOT

11 ALIVE NEED SMALL BOAT

KENNEDY

...Biuku and Eroni regarded themselves as being as much a part of the Allied forces as Kennedy, Evans or anyone else. With a strong sense of responsibility they embarked for Rendova Harbor thirty-eight miles away. They first stopped in Raramana, where they told Benjamin Kevu, the English-speaking scout, about the survivors. Benjamin, knowing Evans was on the move, dispatched another scout to Gomu Island to wait for Evans and give him the news. From Raramana, Biuku and Eroni went on foot to the village of Madou, also on Wana Wana where they picked up John Kari for an overnight paddle to Rendova Harbor.

Evans meanwhile had arrived at Gomu at nightfall and received the verbal message from the scout about the eleven Americans. There was nothing he could do about them immediately. As he had to get his new headquarters set up, he did not transmit any messages that evening. He decided, however, that he would send some of his scouts in a large canoe to Naru in the morning, and that night he penciled a message for them to carry....

Early on Saturday morning, August 7, Biuku, Eroni and John Kari reached Blanch Channel. The Navy had a base at Roviana Island, near Munda, and as this was closer than Rendova the three natives stopped there and showed Kennedy's coconut shell...to an officer. He immediately ordered a whaleboat to take them to the base at Sasavele Island farther down the New Georgia coast, whence they were whisked over to Rendova Harbor in a PT boat>. Lumberi was already in a state of excitement over a message that had just been relayed from Evans. At 9:20am he had radioed KEN:

ELEVEN SURVIVORS PT BOAT ON GROSS IS X

HAVE SENT FOOD AND LETTER ADVISING SENIOR COME HERE WITHOUT DELAY X

WARN AVIATION OF CANOES CROSSING FERGUSON

At 11:30am PWD messaged Evans:

GREAT NEWS X COMMANDER PT BASE RECEIVED A MESSAGE

JUST AFTER YOURS FROM SURVIVORS BY NATIVE X

THEY GAVE THEIR POSITION AND NEWS THAT

SOME ARE BADLY WOUNDED AND REQUEST RESCUE X

WE PASSED THE NEWS THAT YOU HAD SENT CANOES AND

WITHOUT WISHING TO INTERFERED WITH YOUR ARRANGEMENTS

WANT TO KNOW CAN THEY ASSIST X THEY WOULD SEND SURFACE CRAFT

TO MEET YOUR RETURNING CANOES OR ANYTHING YOU ADVISE X

THEY WISH TO EXPRESS GREAT APPRECIATION X

WE WILL AWAIT YOUR ADVICE AND PASS ON

At 12:45pm Evans replied:

COULD ONLY MAN ONE CANOE SUITABLE FOR CROSSING X

NO SIGN ITS RETURN YET X GO AHEAD AND SEND SURFACE CRAFT

WITH SUITABLE RAFT OR DINGHIES X

IF ANY ARRIVE HERE LATER WILL SEND OTHER ROUTE X

PLEASE KEEP ME INFORMED

Evans sent seven of his scouts for Kennedy -- Moses Sesa, Jonathan Bia, Joseph Eta, Stephen Hitu, Koete Igolo, Edward Kodoe and Benjamin Kevu, who was the leader. From the information passed on by Biuku and Eroni on their way back to Rendova the seven knew that the Americans were on Olasana Island but they did not know what part. After a paddle of more than two hours they glided up on a beach without seeing a sign of any survivors. They listened but heard nothing. Dividing into two groups, one circled the island to the right, the other to the left. In the group that was headed to the left Moses Sesa motioned to the men to stop. Footprints ran across into the underbrush. Cautious at first because of the presence of Japanese in the region, the natives followed the footprints to a clearing where they discoverd the survivors. (These seven, as well as Biuku Gasa, Eroni Kumana and John Kari, are alive and in good health in the Solomon Islands today [1961] and remember as one the great moments of their lives in the rescue of "Captain Kennedy" and the crew of his PT boat. The event is celebrated in a folk song that has been sung in the islands for years).

ON HIS MAJESTY'S SERVICE

TO SENIOR OFFICER, NARU IS

FRIDAY, 11PM. HAVE JUST LEARNT OF YOUR PRESENCE ON NARU IS

& ALSO THAT TWO NATIVES HAVE TAKEN NEWS TO RENDOVA.

I STRONGLY ADVISE YOU RETURN IMMEDIATELY TO HERE IN THIS CANOE

& BY THE TIME YOU ARRIVE HERE I WILL BE IN RADIO COMMUNICATION

WITH AUTHORITIES AT RENDOVA &

WE CAN FINALIZE PLANS TO COLLECT BALANCE YOUR PARTY.

WILL WARN AVIATION OF YOUR CROSSING FERGUSON PASSAGE.

A R EVANS LT

R A N V R

Everything about the arrival of Evans's scouts on Olasana Island seemed unbelievable. Kennedy, who had barely smiled in a week, was tickled when handed a communication beginning, "On His Majesty's Service", by a black man naked except for a cloth around his waist. Here he was, bearded, gaunt, unwashed, half-starved, half-naked, blotched with festering coral wounds, castaway on a miserable patch of jungle surrounded by sharks, being greeted as if he were in his father's embassy in London. "You've got to hand it to the British", he said to Ross.

The canoe itself was a cornucopia. Before the gluttonous eyes of eleven famished sailors, yams, pawpaws, rice, potatoes, boiled fish, Chelsea cigarettes and C rations with roast-beef hash poured ashore. Some of the natives scampered up palm trees like monkeys to fetch coconuts. Others collected palm fronds and built a hut for McMahon. Still others lighted three kerosene burners for cooking. His idle period at an end, Mauer stepped in to raise the hash above the level of a C ration. The natives fashioned dishes out of coconut shells and spoons out of palm fronds....

When the meal was over, Benjamin suggested to Kennedy that it was time to leave for Gomu. It was possible for only one American to be hidden in the canoe with seven natives paddling, and since Evans had urged that the "senior" should come, Kennedy had little choice no matter what reservations he might have about leaving his men.

The natives tossed some dead palm fronds into the canoe to conceal him when they got out into Blackett Strait. Looking ahead to the problems of rescue, Kennedy knew it would be difficult to find an opening in the reef at night. As the canoe passed through the reef into Blackett Strait, therefore, he glanced back to get a point of reference on Olasana that he might be able to recognize in the dark. After he felt that he had the location of the opening fixed in his mind he lay down in the middle of the canoe with his feet toward the bow. Benjamin covered him with fronds and knelt by his head, paddling and occasionally chatting with him. Half way to Gomu the paddlers heard the hum of airplane engines. First a single Japanese plane flew in from sea and circled over them and then two more enemy planes, from Vila. The natives were frightened that the Japanese somehow knew about their passenger and would destroy them all.

"What's going on?" Kennedy asked through the fronds. "Japanese planes. Stay down!", Benjamin replied. Jonathan Bia wanted Benjamin to make a friendly gesture to the planes, but Benjamin feared this might only make the pilots suspicious. "Can I look now?" Kennedy inquired. "No, no, no, keep down!", Benjamin snapped. After an argument with Jonathan, Benjamin stood up and waved at the planes. Jonathan was right. Eventually the Japanese flew away, and the natives, five of them Methodists and two Seventh-Day-Adventists, burst into hymns.

Evans meanwhile was watching anxiously from Gomu. When, shortly before 6pm, his binoculars picked up the approaching natives, he was dismayed not to see any Americans in the canoe. Then it dawned on him that of course the natives would have concealed such a passenger. When the canoe touched the sand, Kennedy stuck his head through the palm fronds and smiled at Evans. "Hello", he said "I'm Kennedy". Evans introduced himself, and they shook hands. The coastwatcher was surprised at the youthfulness of his guest and gratified that he was in as good condition as he was. "Come and have some tea", he invited him. They walked back from the beach to an old wooden house on the island. Evans was in shorts. Kennedy was wearing skivvies and was barefoot. Over tea they discussed rescue plans.

Evans showed Kennedy a message from Lumberi, relayed by PWD at 1:51pm:

THREE PT BOATS PROCEED TONIGHT

AND WILL BE AT GROSS ISLAND ABOUT TEN PM X

THEY WILL TAKE RAFTS ETC X

WILL INFORM YOU WHEN WE RECEIVED ADVICE OF RESCUE

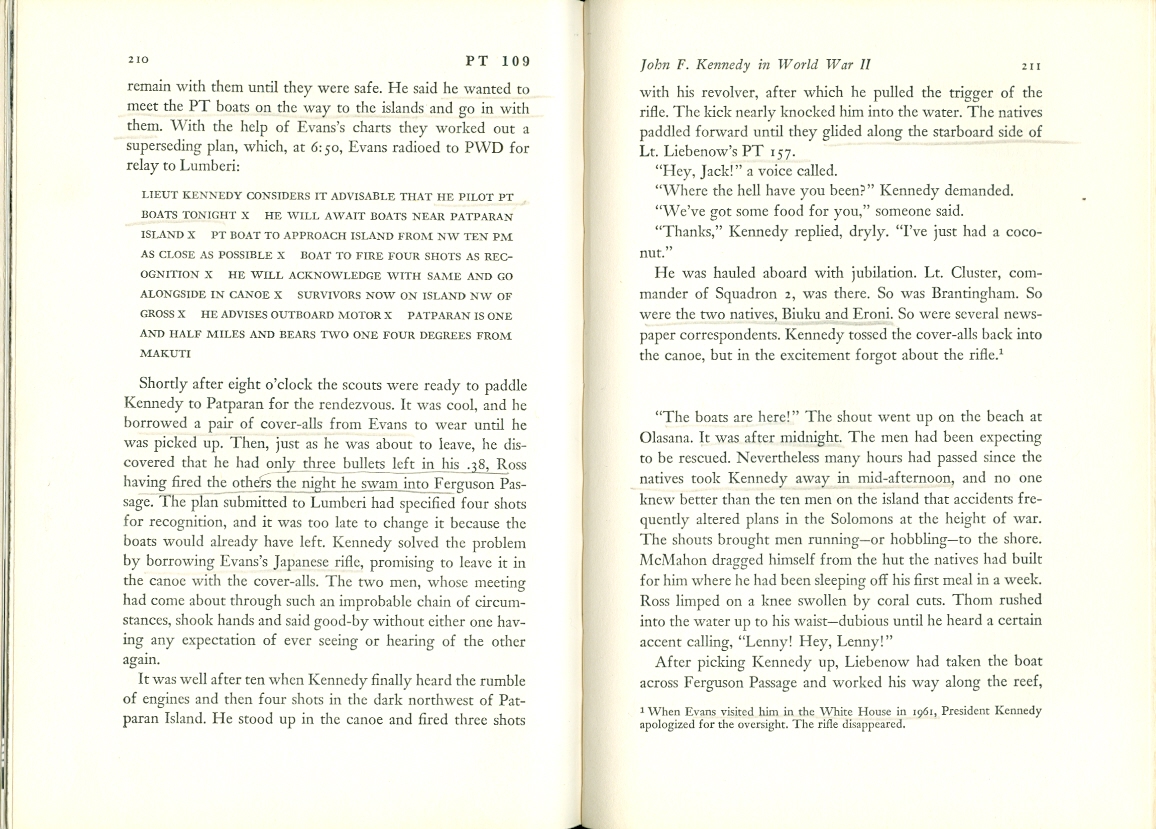

Evans further suggested to Kennedy that the natives paddle him back to Rendova by way of the Wana Wana Lagoon while the PT boats went in to pick up the men. Kennedy would not hear of either plan. It would be difficult, perhaps impossible, for anyone who did not know exactly where they were to find the men in the dark, he argued. Moreover, he said, he was responsible for his men, and it was his duty to remain with them until they were safe. He said he wanted to meet the PT boats on the way to the islands and go in with them. With the help of Evans's charts they worked out a superseding plan, which, at 6:50pm, Evans radioed to PWD for relay to Lumberi:

LIEUT KENNEDY CONSIDERS IT ADVISABLE THAT HE PILOT PT BOATS TONIGHT X

HE WILL AWAIT BOATS NEAR PATPARAN ISLAND X

PT BOAT TO APPROACH ISLAND FROM NW TEN PM AS CLOSE AS POSSIBLE X

BOAT TO FIRE FOUR SHOTS AS RECOGNITION X

HE WILL ACKNOWLEDGE SAME AND GO ALONGSIDE IN CANOE X

SURVIVORS NOW ON ISLAND NW OF GROSS X HE ADVISES OUTBOARD MOTOR X

PATPARAN IS ONE AND HALF MILES AND BEARS TWO ONE FOUR DEGREES FROM MAKUTI

Shortly after 8:00pm the scouts were ready to paddle Kennedy to Patparan for the rendezvous. It was cool, and he borrowed a pair of cover-alls from Evans to wear until he was picked up. Then, just as he was about to leave, he discovered that he had only three bullets left in his .38, Ross having fired the others the night he swam into Ferguson Passage. The plan submitted to Lumberi had specified four shots for recognition, and it was too late to change it because the boats would already have left. Kennedy solved the problem by borrowing Evans's Japanese rifle, promising to leave it in the canoe with the cover-alls. The two men, whose meeting had come about through such an improbable chain of circumstances, shook hands and said good-by without either one having any expectation of ever seeing or hearing of the other again.

It was well after 10:00pm when Kennedy finally heard the rumble of engines and then four shots in the dark northwest of Patparan Island. He stood up in the canoe and fired three shots with his revolver, after which he pulled the trigger of the rifle. The kick nearly knocked him into the water. The natives paddled forward until they glided along the starboard side of Lt Liebenow's PT 157. "Hey, Jack!" a voice called. "Where the hell have you been?" Kennedy demanded. "We've got some food for you", someone said. "No thanks", Kennedy replied, dryly. "I've just had a coconut".

Kennedy was hauled aboard with jubilation. Lt Cluster, commander of Squadron 2, was there. So was Brantingham. So were the two natives, Biuku and Eroni. So were several newspaper correspondents. Kennedy tossed the cover-all back into the canoe, but in the exciterment forgot about the rifle.

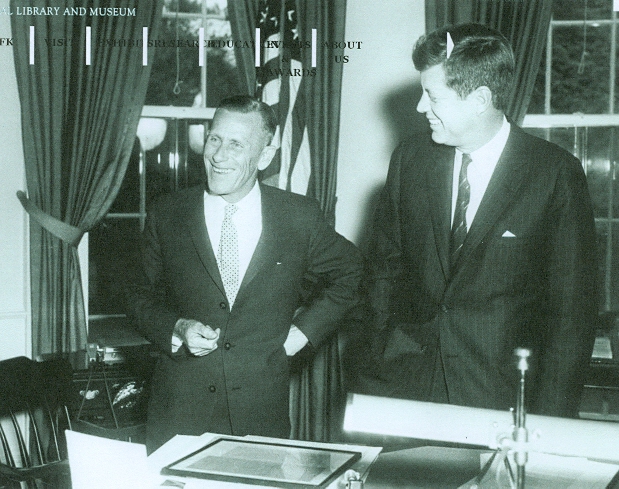

When Evans visited him in the White House in 1961, President Kennedy apologized for the oversight. The rifle disappeared....

~ end quoting PT 109 by Donovan ~

SOLOMON NATIVES HID JFK IN CANOE

JFK PT-109 MOVIE STAR MAGUIRE

(radioman next to skipper when PT-109 hit)

JFK PT-109 MECHANIC ZINSER

(Zinser, on watch below, started the engines)

Emails, Oct 20, 2017

watch PT 109 MOVIE & PT 109 SONG

JFK O CAPTAIN! MY CAPTAIN!

watch Oz Evans on To Tell The Truth

OZ COASTWATCHER EVANS RESCUED JFK

O'REILLY BOOK KILLS JFK & EVANS

Email, Nov 10, 2014

Ministry of Truth & Prolefeed & Prostitute Writers

watch PT 109 SONG, YouTube (at 43 seconds Evans is mentioned: "And on the coast of Kolombangara, looking through his telescope, Australian Evans saw the battle, for the crew had little hope...)

watch REG EVANS ON TO TELL THE TRUTH, May 1, 1961, YouTube (One of these men has come 10,000 miles to meet a famous person he rescued almost 18 years ago. Only one of these men is the real Reg Evans -- the other two are imposters and will try to fool this panel. AFFIDAVIT: "I, Reg Evans, during World War Two worked for Australian Navy Intelligence. My job was to sit on an island behind the Japanese lines and report by radio on the movements of enemy ships and planes. One day I received word that the crew of a sunken American PT boat was stranded on a small island nearby. Natives brought the skipper of the group to me in a canoe. I offered this officer immediate rescue but he preferred to stay with his men. By radio I arranged for them to be picked up by American PT boats. I have not seen this American navy officer for more than 17 years. I will meet him again this week in the White House in Washington, DC. His name is John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

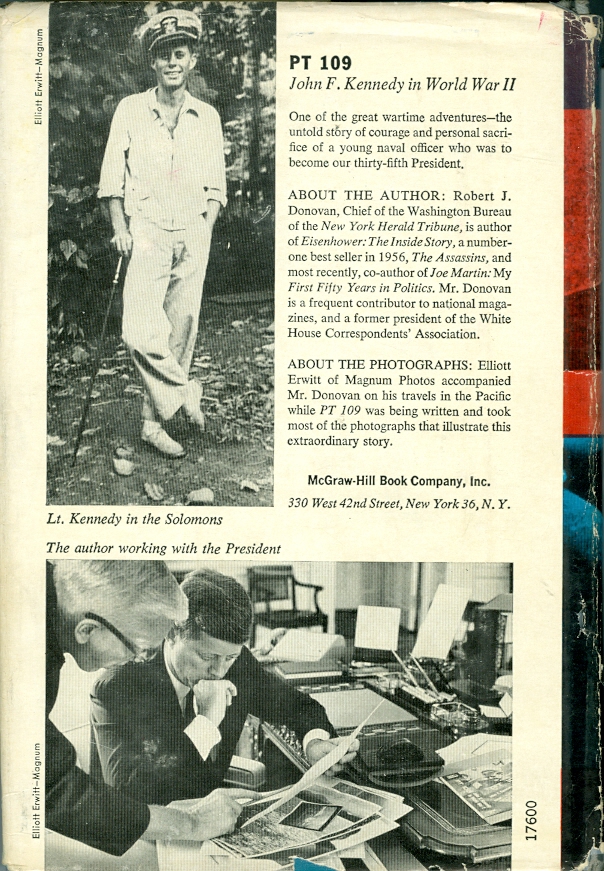

Painting: "The Beach at Gomu", by Norman Baer, JFK Library ( Description: President John F Kennedy visits with A.R. "Reg" Evans", an Australian Coast Watcher from New South Wales who, while stationed on the Solomon Islands during World War II, helped rescue the crew of PT 109 (including then-Lieutenant John F Kennedy). Mr Evans...holds the painting depicting Lieutenant Kennedy in a canoe with native islanders in the Solomon Islands. Oval Office, White House, Washington, DC

Painting: "The Beach at Gomu", by Norman Baer, JFK Library ( Description: President John F Kennedy visits with A.R. "Reg" Evans", an Australian Coast Watcher from New South Wales who, while stationed on the Solomon Islands during World War II, helped rescue the crew of PT 109 (including then-Lieutenant John F Kennedy). Mr Evans...holds the painting depicting Lieutenant Kennedy in a canoe with native islanders in the Solomon Islands. Oval Office, White House, Washington, DC

Reliving Old Memories, National Geographic (Following John F Kennedy's election as President, he met in the oval office with a key player in the PT 109 saga, Arthur Reginald Evans. Evans, a coastwatcher and Lieutenant in the Australian Navy, witnessed a fireball in Blackett Strait about the time of the nighttime collision between Kennedy's boat and the Japanese destroyer. Evans became instrumental in the rescue of Kennedy and his men.)

Reliving Old Memories, National Geographic (Following John F Kennedy's election as President, he met in the oval office with a key player in the PT 109 saga, Arthur Reginald Evans. Evans, a coastwatcher and Lieutenant in the Australian Navy, witnessed a fireball in Blackett Strait about the time of the nighttime collision between Kennedy's boat and the Japanese destroyer. Evans became instrumental in the rescue of Kennedy and his men.)

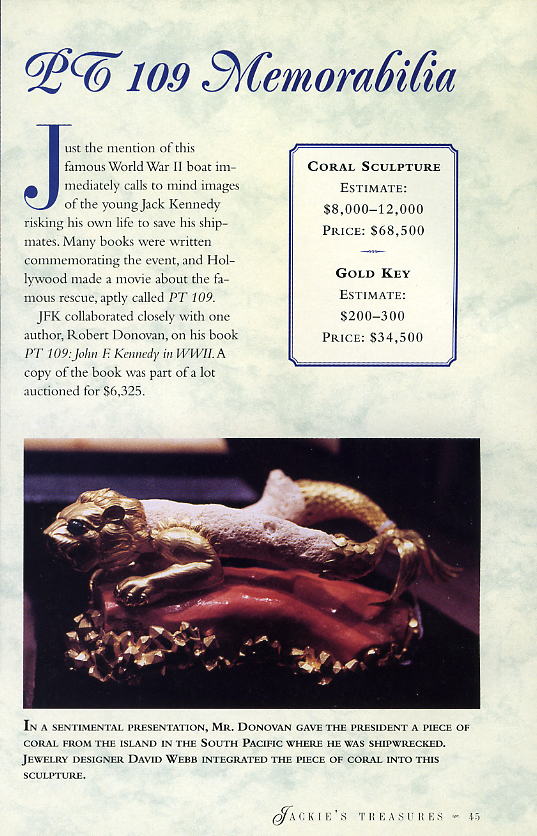

PT 109 Memorabilia, Coral Sculpture, Price $68,500 (Just the mention of this famous World War II boat immediately calls to mind images of the young Jack Kennedy risking his own life to save his shipmates. Many books were written commemorating the event, and Hollywood made a movie about the famous rescue, aptly called PT 109. JFK collaborated closely with one author, Robert Donovan, on his book PT 109: John F Kennedy in WWII. A copy of the book was part of a lot auctioned for $6,325.... In a sentimental presentation, Mr Donovan gave the President a piece of coral from the island in the South Pacific where he was shipwrecked. Jewelry designer David Webb integrated the piece of coral into the sculpture.)

PT 109 Memorabilia, Coral Sculpture, Price $68,500 (Just the mention of this famous World War II boat immediately calls to mind images of the young Jack Kennedy risking his own life to save his shipmates. Many books were written commemorating the event, and Hollywood made a movie about the famous rescue, aptly called PT 109. JFK collaborated closely with one author, Robert Donovan, on his book PT 109: John F Kennedy in WWII. A copy of the book was part of a lot auctioned for $6,325.... In a sentimental presentation, Mr Donovan gave the President a piece of coral from the island in the South Pacific where he was shipwrecked. Jewelry designer David Webb integrated the piece of coral into the sculpture.)

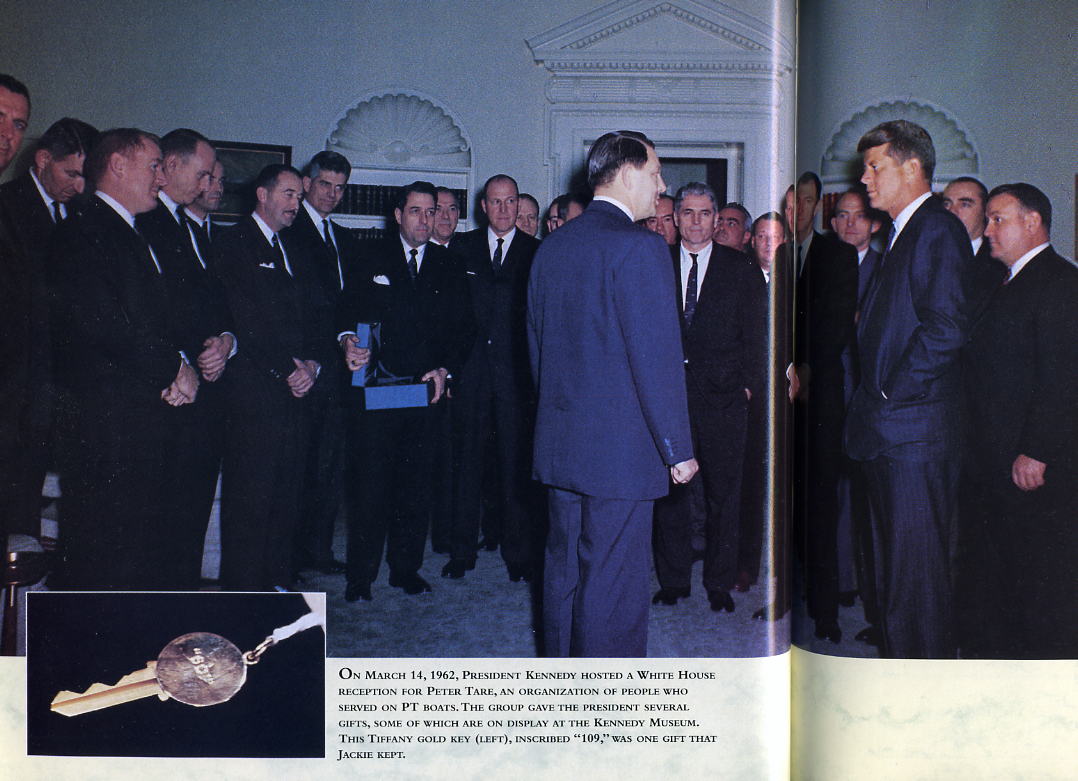

On March 14, 1962, President Kennedy hosted a White House reception for Peter Tare, an organization of people who served on PT boats. The group gave the President several gifts, some of which are on display at the Kennedy Museum. The Tiffany cold key (left), inscribed "109", was one gift that Jackie kept.

On March 14, 1962, President Kennedy hosted a White House reception for Peter Tare, an organization of people who served on PT boats. The group gave the President several gifts, some of which are on display at the Kennedy Museum. The Tiffany cold key (left), inscribed "109", was one gift that Jackie kept.

JFK SOLOMON SWIMS SAVED SURVIVORS (...Kumana and Gaza got into their canoe and started on their journey with the coconut. They stopped at WANA WANA island and told the native coastwatcher there that eleven Americans were alive on OLASANA and needed food and water desperately -- then they proceeded on toward RENDOVA. After Kumana and Gaza left WANA WANA the native coastwatcher there sent native scouts in a canoe to a little island in the middle of Blackett Strait -- GOMU -- to wait there for the Australian coastwatcher -- Evans -- who would be moving his base there that night from his previous lookout on KOLOMBANGARA island (from where he'd seen PT 109 explode Sunday night and debris on Monday morning and had radioed a report to USA headquarters in Guadalcanal and told his native scouts to be looking for any survivors). Upon hearing from the scouts that survivors had been found on OLASANA Evans radioed the news to Guadalcanal with word that native scouts were on the way to RENDOVA with a message. The next morning -- Saturday, August 7th -- Evans sent seven natives in a canoe to OLASANA with food and drinks for the survivors and a note to the senior officer -- that was JFK -- telling him to return with the natives to GOMU to help arrange the rescue. Around 6pm that evening, after the survivors had eaten a feast prepared by the natives, JFK got into the canoe for the trip to GOMU. He crouched on the floor, covered in palm leaves, to hide from Japanese airplanes flying overhead. Two hours later the canoe pulled up to GOMU and JFK popped out from under the palm leaves and introduced himself to Evans -- who invited him into his hut for tea and talk....)

Arthur Reginald Evans, born 14 May 1905, died January 1989 at age 84, Wikipedia (Arthur Reginald Evans, DSC was an Australian coastwatcher in the Pacific Ocean theatre in World War II. He secretly manned an observation post atop Mount Veve volcano on Kolombangara, a small circular volcanic island, while over 10,000 Japanese soldiers were camped at Vila, on the island's southeastern tip. On 2 August 1943 he spotted the explosion of John F Kennedy's boat PT-109, although he did not realise at the time it was an Allied loss. However, he later received and decoded the message that the PT-109 was missing, and dispatched Solomon Islander scouts Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana in dugout canoes to find the crew. He met with John F. Kennedy after he became President of the United States, visiting the White House on 1 May 1961.

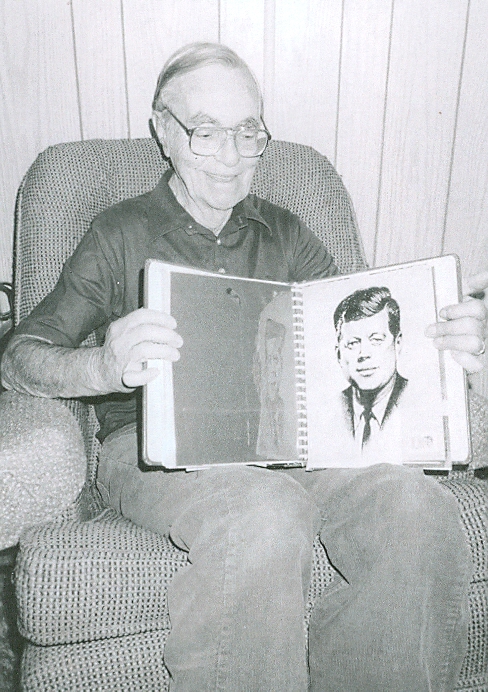

Patrick McMahon, whom John F Kennedy had rescued on the PT-109 during World War II,

at his Encinatas California home in 1983

McMahon died in Encinitas in February 1990 at the age of 84

McMahon Remembering JFK and PT-109 Heroism

"I owe it to my skipper to tell about the PT-109. I owe it to his memory."

by Sharon Whitley Larsen*, San Diego, November 21, 2013

It was in 1983 when I first met Patrick McMahon, whom John F. Kennedy had rescued on the PT-109 during World War II. He was a retired Cathedral City, California mail carrier, then postmaster, who had moved to Encinitas in 1975 with his wife, Rose.

McMahon always fondly referred to Kennedy as "the skipper". They remained friends until that fateful day in November 50 years ago. McMahon had been an automotive repairman in Detroit in 1941 when, at age 37, he enlisted in the Navy. It was in the Solomon Islands that he was assigned to the PT-109, commanded by 26-year-old Kennedy. "I remember when I first met the skipper I couldn't believe how thin he was. He must have weighed only 135 pounds. He was always hungry!" He recalled how JFK "had confidence in his men; his crew loved him. He would do anything for anyone".

Shortly past midnight on August 2, 1943, the Japanese destroyer Amagiri rammed the PT-109, slicing it in half, instantly killing two of the 13 crew members. McMahon suffered second- and third-degree burns (from which he fully recovered). The surviving crew decided to swim to a nearby island. McMahon was in terrible pain. "The skipper came over to me and said, 'Mac, you and I will go together'. I said, 'I'll just keep you back. You go on with the other men -- don't worry about me'. Exasperated, the skipper cried out, 'What in the hell are you talking about? Get your butt in the water!' The skipper swam the breast stroke, carrying me on his back, with the leather strap of my kapok clenched between his teeth. It was daylight and it took about four hours to swim the three miles to the island".

Later they swam to a larger island. "It took several hours to reach it, and when we finally arrived on the land, the skipper was physically ill, retching and vomiting. Many of the crew were frustrated and despondent". JFK ended up spending some 30 hours in the shark-infested water during the ordeal, swimming out to sea in an attempt to attract the attention of another PT boat. At times, showing his humor, Kennedy would say, 'We're going to get back if I have to tow this island back!".

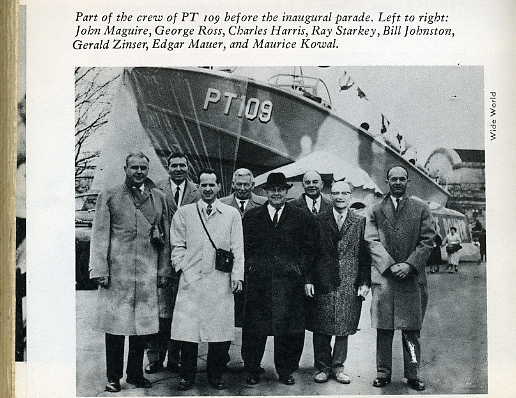

With the help of some natives, the crew was discovered and rescued several days later. During McMahon's hospital recuperation, JFK wrote Rose McMahon on August 11, 1943: "Your husband is alive and well. He acted in a way that has brought him official commendation -- and the respect and affection of the officers and crew with whom he served". Over the next two decades, the two friends corresponded by mail and visited in person. The McMahons visited the Kennedy compound at Hyannis Port and McMahon was thrilled to attend the inauguration and parade. "All the crew rode on the PT-109 float in the parade as a surprise to the skipper. As we passed by the presidential reviewing stand, Kennedy stood up, grinned, whipped off his silk top hat, and gave us the skipper's signal: 'Wind 'em up, rev 'em up, let's go!."

McMahon cherished a signed framed photo of the PT-109 inaugural float: "For Patrick McMahon -- with the warm regards of his old skipper -- John F Kennedy". McMahon would see JFK when he visited Palm Springs. The Secret Service would call him to leave his mail rounds and go to the airport, where he would sit in a limo and wait for the president. The last time he saw his skipper was in 1961. "After his plane landed, he sat in the car with me, shook my hand, and repeated the same thing that he had said to me often throughout the years, 'If there's anything you ever need, Mac, let me know -- it will just take a telephone call". After what he did for me -- the President of the United States saved my life -- I could never have asked him for anything". In 1964, Bobby Kennedy congratulated McMahon on his promotion to Cathedral City Postmaster: "The president was always so fond of you and he would have wanted this for you also". McMahon died in Encinitas, California in February 1990 at the age of 84.

McMahon remembering JFK and PT-109 heroism, by Sharon Whitley Larsen, a freelance writer who saw JFK's motorcade when he visited San Diego in June 1963. She was in the seventh grade at Lewis Junior High on November 22, 1963, when she learned of his assassination)