Why does a band with an on-reserve population of 1,100 people —

about the same as your average 25-storey urban apartment building —

need a 14-member council and 46 senior staff to keep it running?

HEAP BIG SALARY INDIAN CHIEFS

First Nations are heavily subsidized by Canadian taxpayers....

This type of abuse of public funds is completely inexcusable.

When so many aboriginal Canadians live in squalor,

how can their leadership justify living large?

Why are so many pulling in huge paycheques?

Alberta native chief makes 30% more than premier

(Secrecy the norm in native politics)

by Kevin Libin, National Post, Apr 21, 2010

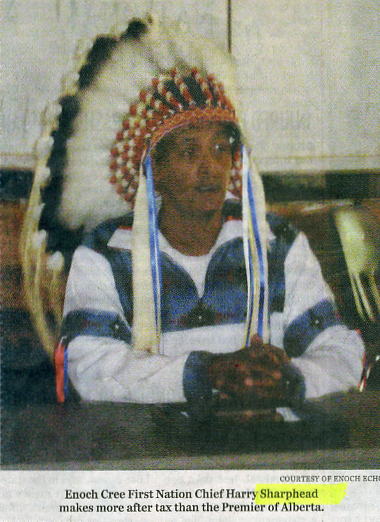

There are reasons Alberta's Ed Stelmach might envy the chief of the Enoch Cree First Nation that sits on Edmonton's western flank, just 17 kilometres from the Premier's own office. Although Mr. Stelmach's Cabinet tried quietly to hike their salaries dramatically in 2008, making him the highest paid premier in the country, the raises didn't stay quiet: Snoopy reporters found out by searching online government records, and the voters' outrage at the stunt still infects the Progressive Conservative government's popularity like a lingering cold sore. Harry Sharphead is luckier. First Nation governments needn't post financial disclosures on any irksome web-sites, and band council meetings close their doors as often as they open them -- which might explain another reason the Premier might have to be jealous of the chief: For managing a band of scarcely 2,000 people, Mr. Sharphead makes, after taxes, 30% more than the head of Canada's fourth-largest province.

This information comes from the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, which learned it only thanks to a "brown envelope" passed its way with a note from an anonymous Enoch Cree band member who had been unable, after repeated attempts, to get his own band's financial records from council, or from the Indian Affairs department. One leak after another brought it to light. This is, often, the only way First Nations people find out how their politicians spend band money, and how much of it they're taking home with them. "So often, the story we hear from people on reserves is they ask for this information and they're denied.... They'll ask their chiefs and they'll say, 'Buzz off,' " says Colin Craig, the federation's Prairie director. Politicians in Canada's federal, provincial and municipal governments, as well as Crown corporations, have their earnings publicly disclosed, Mr. Craig points out. Not so for public officials on reserves.

To his credit, Mr. Sharphead, elected in July, is a bargain compared with his predecessor: Chief Ron Morin was, at one point, paying himself $327,712 out of band funds, which -- because on-reserve incomes are tax exempt -- was roughly the equivalent to a $515,000 income off reserve. Mr. Sharphead has cut that twice now, most recently in November when, in a letter to the Enoch Cree finance manager, he said he would take only $180,000 a year -- about the same as a $274,000 income earned off-reserve, still $60,000 larger than the Alberta Premier's pay-cheque. "Equality amongst our people is critical to the growth and solidarity of our community," wrote Mr. Sharphead, who did not return phone calls. "We must lead by example." Yet average Enoch Cree members, according to the CTF, were reportedly as in the dark about the salary revisions as they were about the original arrangements, which also saw an average salary of $175,725 for the 10 band councillors, and six-figure incomes for a third of its senior bureaucrats.

Meanwhile, just a third of Enoch Cree band members have jobs; among those who do, average earnings, according to the most recent data available, were just $16,000 a year. The Enoch Cree band has run up in recent years millions in debt. Leaked band records show the Enoch Cree receive about $9-million a year in federal funding. "I am writing this letter out of pure frustration," wrote the CTF's source. "I live on the Enoch Cree Nation and we should have no problem providing for our people. The problem is the greed of our leadership and the lack of motivation. They know that there is nothing we can do to change the policies. We are under a different system than the real world.... We have nowhere to turn."

In December, it was another brown envelope to the CTF that revealed that band councillors on Manitoba's Peguis First Nation were earning up to a quarter-million tax-free dollars. Technically, concerned band members do have somewhere to turn: Indian Affairs and Northern Affairs Canada requires, in funding agreements with First Nations, that bands provide records to any member wanting them. Councils don't necessarily comply, and anyone getting too pushy risks ending up on council's bad side, potentially affecting when they get off the waiting list for home repairs, or a job with a band-owned business.

While First Nations are heavily subsidized by Canadian taxpayers, and must file financial reports with the ministry, the government cannot release them publicly. A 1988 court case ruled that the records might reveal details of income from "proprietary" band-owned businesses -- the Enoch Cree has oil revenues, owns a casino and a golf course, and a few retailers (their gas bar recently slashed employees' wages by 30%) -- and so were exempt from access to information requests. However, Mr. Craig believes there is nothing to prevent an interested federal government from changing laws to allow it. But in the peculiar world in which First Nations exist, where funds come from a third party to be redistributed by Ottawa, band councils don't necessarily feel the fiscal accountability to members as do elected officials off-reserve, who know it's voters who pay their salaries. "Even on most of the best-run reserves, most money flows from other sources, so voters don't make a connection between policy and reaching into their own pockets," says Tom Flanagan, a University of Calgary political scientist and co-author of Beyond the Indian Act: Restoring Aboriginal Property Rights. "So, it's more demands -- 'What can you do for me?' -- rather than 'How can you prudently manage affairs so I don't have to pay as much?'" About a quarter of First Nations levy some tax, he says, but usually on leaseholders (like mining companies), who often aren't members. Rarely is it enough of the financial picture that members feel it in their pocketbook when councils act irresponsibly. Not that this is necessarily the case with Mr. Sharphead. Mr. Flanagan argues that it's possible that Enoch Cree band members might think their chief is worth every penny he earns. Of course, without the help of that anonymous note, few band members would have been able to make that judgment.

Big spending and fake democracy on native reserves

National Post, Apr 21, 2010

This week, the Canadian Taxpayers Federation (CTF) reported that Chief Harry Sharphead of the Enoch Cree First Nation in Alberta — a community whose on-and-off-reserve populations totals about 2,000— earns $180,000 per year. His predecessor, former chief Ron Morin, took in a whopping $250,000. As aboriginal Canadians are exempt from tax for their on-reserve labour, Mr. Sharphead earned the equivalent of $274,000 a year, while Mr. Morin pocketed $388,000. Meanwhile, Ed Stelmach, the Premier of Alberta (whose population is roughly 2,000 times that of the Enoch Cree First Nation) took home just $214,000 a year — on which he pays taxes. But there’s more. Of 14 Enoch Cree council members, all but two had annual incomes over $75,000 in 2006-07, the year referenced by the band documents cited by the CTF. The three top-earning councillors pulled in $178,000, $177,000 and $155,000, tax-free, respectively. Together, the council and chief pocketed $1.7-million a year, while 46 other "senior staff" raked in $3.3-million, for a total of $5-million in remuneration.

According to documents publicly available on the website of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (DIAND), that same year, the Enoch Cree band spent just under $11.5-million in federal funding on everything else for its on-reserve population of 1,100 people (as per the 2001 census). That includes health, education, as well as $219,000 for “band employee benefits.” In 2001, average income for the 735 persons over 15 years of age on the Enoch Cree reserve was a mere $12,770. Only 430 of these persons actually earned employment wages, with an average annual salary of just over $16,000. This suggests that almost the entire population subsists at or below the poverty line — save for the band council and senior staff.

This type of abuse of public funds is completely inexcusable in any context, but even more so here. When so many aboriginal Canadians live in squalor, how can their leadership justify living large? At the same time that native leaders decry a lack of funding for water, education and other essentials for their people, why are so many pulling in huge paycheques? Putting aside the profligate waste of cash, what are all these people doing? Why does a band with an on-reserve population of 1,100 people — about the same as your average 25-storey urban apartment building — need a 14-member council and 46 senior staff to keep it running?

Stories like this crop up with disturbing regularity. But in truth, we don’t know exactly how many reserves are spending their money in such an irresponsible manner, because the law currently does not require aboriginal bands to submit to the same standards of accountability and transparency as all other senior Canadian officials — an absolutely unconscionable loophole whose only conceivable function is to spare aboriginal leaders embarrassment. The federal government requires public disclosure of salaries, travel and other expenses for its MPs and senior staff. It should do the same for band council chiefs, councillors, and other native leaders. These figures should be posted on the Internet, where the public can see them.

Beyond this, there is a broader lesson from Enoch Cree. Whenever the case is made for greater self-government for First Nations, it always is assumed that Ottawa will continue to send big cheques every year: i.e., band leaders would get more power, but on the federal government’s dime. The problem is that "self-government" is a contradiction in terms when someone else is paying the bill: Without the political discipline that comes with being accountable to taxpaying voters, politicians operate in a world without constraints. Since the Enoch Cree band councillors’ salaries are being paid by Ottawa anyway, why should rank-and-file Enoch Cree residents get up-in-arms about it? It’s not their money. When it comes to native policy, the famous adage "no taxation without representation" can be flipped on its head: "no representation without taxation."

Reader Marcel says the chief and council of the Cold Lake First Nations are living it up with no accountability

Alberta native chief makes 30% more than premier (aboriginals exempt from paying taxes), National Post, Apr 21, 2010

Big spending and fake democracy on native reserves, National Post, Apr 21, 2010

ALONE AGAINST TERRORIST INDIANS

ME HEAP BIG INJUN, YouTube (...And by the way, we want a new deal. No more 50/50, from now on you get 25% and my people get 75%.... We're a reasonable bunch of Indians....)

BC Indian chief & councillors each take $800,000 (from gov't cash payout to 230-member band) & American Indian tribes won't vote for Palin (she allows drilling/fishing/hunting on Native land) & Palin is colour-blind when governing (treats Native constituency same as all Alaskans). AOL/NavajoTribe/AP, Sep 28, 2008

INDIAN LAND CLAIMS DISBELIEVED

Jackie Jura

~ an independent researcher monitoring local, national and international events ~

email: orwelltoday@gmail.com

HOME PAGE

website: www.orwelltoday.com