ORWELL'S TB DOC O'SHAUGHNESSY

As the consultant surgeon at the Preston Hall Sanatorium,

Dr Laurence O'Shaughnessy visited Orwell once each week and made every effort

to determine whether his brother-in-law was, in fact, suffering from tuberculosis.

At the very time that he was attending his sister's husband,

the doctor was in the middle of writing, with two other men,

an authoritative textbook on the disease.

To Orwell Today,

re: VISITING ORWELL'S ANIMAL FARM

I have only recently come across your excellent website.

I was impressed by your pilgrimage to Barnhill, Wallington and other places associated with the great man, but would like to question your association of Manor Farm Wallington as the inspiration for the location and description for Animal Farm. I would like to suggest you Google Preston Hall Aylesford Kent and read the description and history therein.

Preston Hall was the so-called Sanatorium to which Eric Blair was admitted in 1938. In fact it was a fully fledged Chest Hospital, and the most advanced centre for the treatment of TB. Eric's brother-in-law was a consultant there and my late father was the Chief Radiographer. My father ended up looking after Eric's dog Marx for the duration of his stay as dogs were not allowed in the Hospital and Grounds.

After a recovery in his condition, Eric spent most of his time working in the Hospital Farms located in the grounds. The farm complex was called Manor Farm, a name that goes back many centuries and named after Preston Hall Manor. There were three farms namely Pig, Game and Horticultural, with associated Barns, Sheds, Cottages and outbuildings surrounded by large pastures, Ponds and close to a river stream. The Pig Farm was particularly large, and although Eric had kept some animals in the past I don't think this extended to Pigs.

I thought the pictures you show of Manor Farm Wallington made this an unlikely Pig Farm, but I am curious and will pay a visit later this year. Of course Animal Farm could be an amalgam of all these influences but I strongly suspect Preston Hall Aylesford Kent was the main one. Unfortunately the Manor Farm is no longer there but the Hall and Hospital buildings are still very much in use.

-Tim Rothwell

Greetings Tim,

Thanks for your insights into aspects of Orwell's life while he was staying at Preston Hall Tuberculosis Sanatorium. It's amazing to be hearing from someone who's father helped look after Orwell by taking the all-important X-Rays (and even looking after Orwell's dog) while he was there. I wonder if you were born by then and, if so, have memories of that time. Orwell was a patient at Preston Hall for five and a half months, from mid-March to the beginning of September 1938.

I googled Old Preston Hall and Preston Hall Hospital in Ayelsford, Kent

I learned that the original Preston Hall manor house was built for a lord in the 11th century - before William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings in 1066 - and then torn down and rebuilt by a railroad magnate in the mid 1800s. Then, during World War One, Preston Hall was turned into a hospital for wounded soldiers coming back from across the English Channel. After World War One it remained a hospital, and by Orwell's time there - just before World War Two - it was the best war veterans' hospital in England and had some of the best doctors in the country (including, of course, Orwell's wife's brother, Dr Laurence O'Shaughnessy).

I had never heard before (in any of the biographies or in letters Orwell wrote from there) that there was a farm attached to the Preston Hall sanatorium - let alone one named "Manor Farm" - and that Orwell had worked there while recuperating. But he does mention, in a letter written toward the end of his stay there, that he was spending most of his time outdoors.

As you say, it could have been Manor Farm at Preston Hall that Orwell had partially in mind when he wrote ANIMAL FARM. But he'd also be thinking - probably more so - of the Manor Farm at Wallington which, actually, DID have pigs. Also, keep in mind that the Manor Farm in ANIMAL FARM wasn't a huge farm like Preston Hall's - but just a family-sized farm run by Mr Jones. The real Manor Farm in Wallington - during Orwell's time - was owned (according to Bowker's Inside Goerge Orwell biography) by a Mr John Innes. (I just now noticed that the first two and last three letters of his full name spell 'Jones').

Orwell's letters from Preston Hall can be found in AN AGE LIKE THIS: 1920-1940 (the first volume of the 4-volume set of his collected essays, journalism and letters). The earlier letters, starting shortly after he'd been admitted in March 1938, are addressed from "Jellicoe Pavillion, Preston Hall" and then the later ones are addressed from "New Hostel, Preston Hall".

Nor had I been aware, until you mentioned it, that Orwell's dog Marx had been with him at Preston Hall for awhile. This his how Eileen, Orwell's wife, describes Marx in a letter she wrote from Wallington - on New Year's Day, 1938 - to a friend she went to Oxford College with. By the sounds of it, your father would have had his hands full looking after Marx.

The excerpt is from letters published in THE LOST ORWELL by Peter Davison:

"...We also have a poodle puppy. We call him Marx to remind us that we had never read Marx and now we have read a little and taken so strong a personal dislike to the man that we can't look the dog in the face when we speak to him. He, the dog, is a French poodle, supposed to be miniature and of prize-winning stock, with silver hair. So far he has black and white hair, greying at the temples and at four and a half months is rather larger than his mother. We think however he may take a prize as the largest miniature. He is very appealing and has a remarkable digestion. I am proud of this. He has never been sick, although almost daily he finds in the garden bones that no eye can have seen these twenty years and has eaten several rugs and a number of chairs and stools. We weren't going to clip him, but he has a lot of hairs which are literally dripping mud on the dryest day - he rolls on every cushion in turn and then drips right through my lap - so we thought we would clip him a little, but now we shall never get him symmetrical till we shave him. Laurence [her brother the doctor] bears with him in a remarkable way and has never scratched even his nose... "

[end quoting from The Lost Orwell by Davison]

At the time Eileen wrote this letter, three months before Orwell was admitted to Preston Hall in March 1938, she and Orwell had been married for a year and a half, and in that time period, Orwell had almost completely destroyed his health.

The day after their wedding in Wallington in June 1936 (at the reception of which they'd served Ayelsford Duck) Orwell had gone right back to work writing THE ROAD TO WIGAN PIER. Then immediately after sending it to the publisher in December 1936, he'd gone to Spain (Eileen followed soon after) and spent six months there fighting alongside Spanish socialists defending their coalition government against overthrow by communist-capitalist-backed fascist Franco.

Eileen was working in the Independent Labour Party office in Barcelona, but visited Orwell at the front, as seen in the photo above. Shortly after that, in May 1937, Orwell got shot through the throat, and it was a miracle he lived - the bullet travelling so fast it cauterized the wound as it passed through his neck. The doctors said he'd never talk again - one of his vocal chords having been severed - but surprisingly his voice did come back, although much weaker than before. Eileen sent a medical report to her brother for his consultation. The bullet also caused nerves in Orwell's shoulder to be pinched and the pain shooting down his right arm was so severe he couldn't sleep and had to have it in a sling for well over a month - thus losing the use of his writing hand. Then, finally, the pain went away and he could use his arm again but the tips of his fingers remained numb long after. Then in June - after hiding from Stalin's secret police, the KGB (who were throwing Orwell's militia compatriots into prison and executing them) - Orwell and Eileen escaped into France and home to England.

Once back in Wallington, Orwell worked non-stop writing HOMAGE TO CATALONIA - his book about the Spanish Civil War and his experiences there - in between planting the vegetable garden, looking after the animals (chickens, goats, dog, cat) and writing articles and reviews of, among other things, other people's books on the Spanish Civil War. But his articles, and even some of his reviews, were refused publication by all the main newspapers and magazines because they exposed Stalin's alliance with Franco and Communism's betrayal of the Socialist government. This suppression of the truth enraged Orwell and caused him incredible stress, on top of worrying about finding a publisher for his book. And sure enough, HOMAGE TO CATALONIA was rejected by Victor Gollancz, his previous publisher, but accepted, finally, by Warburg & Warburg - and came out in April 1938.

Meanwhile Eileen, who prior to marrying Orwell had been pursuing an advanced degree in psychology and living with her brother and his wife - also a doctor - in their home in Greenwich Park, London, was burning the candle - literally - at both ends. Their house in Wallington was medieval-like in its primitiveness - no electricity, no hot water, no inside toilet, no real stove to cook on (just Calor gas) and no functioning fireplace for heat (just a little oil-burner in the kitchen). But still - on top of all the housework and helping Orwell in the garden - she was not only proof-reading and doing the final typing of Orwell's book - by candle-light - but also proof-reading and typing the final copy of her brother's latest tuberculosis textbook. For details on how Orwell met Eileen, and then their life after they got married, go to ORWELL'S 77 PARLIAMENT HILL & ORWELL'S LIFE IN WALLINGTON & VISITING ORWELL'S WALLINGTON HOUSE.

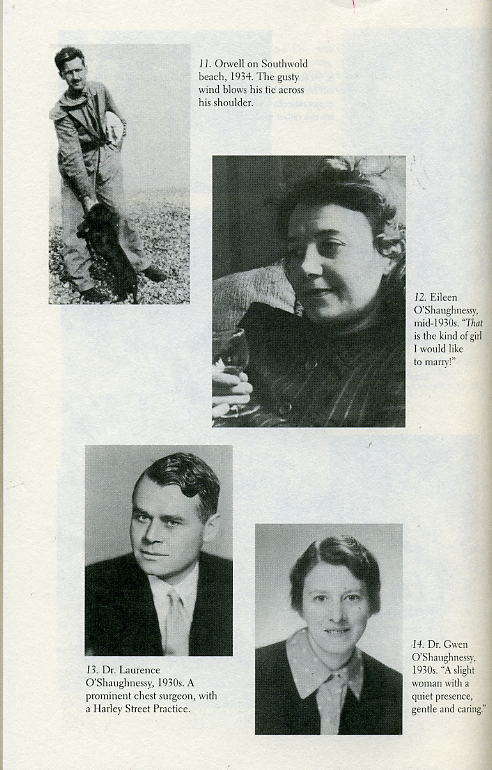

The first photo above is of Orwell, leaning on the gate of their little house in Wallington. Notice the horseshoe hanging above the front door (which was about two feet shorter than Orwell). Next is Eileen with a school friend and then years later with her brother Laurence's baby. The next is Orwell on the beach in Southwold in 1934, shortly before he met Eileen in London in February 1935. Next is of Eileen, with a caption describing what Orwell said to a friend when he first met her, ie "That is the kind of girl I would like to marry!". On the bottom left is her brother, Dr Laurence O'Shaughnessy, "a prominent chest surgeon, with a Harley Street Practice". Bottom right is his wife Dr Gwen O'Shaughnessy who later, through her medical practice, found the baby that Eileen and Orwell adopted in June 1944.

Above are photos of Eileen and Orwell with their son Richard Horatio Blair, taken shortly after they moved into the flat in Islington, North London - and which Orwell used as the model for Winston Smith's flat in "1984". See 27B CANONBURY SQUARE & ORWELL THE FAMILY MAN.

Here's an excerpt from Michael Shelden's ORWELL: THE AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY describing Eileen and her brother Laurence O'Shaughnessy:

"This woman, who would indeed become George Orwell's wife, was an exceptional person. She came from a proud Irish family who had come to England in the early nineteenth century and had settled on the Tyneside. The daughter of a Collector of Customs, she was born on 25 September 1905 in South Shields. There was only one other child in the family, her older brother Laurence, and she was devoted to him. Both children received excellent educations. He studied medicine at the University of Durham and in Berlin, and was the winner of four scholarships. At the age of twenty-six he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Eileen was educated at Sunderland High School, and then won a scholarship to one of the women's colleges at Oxford - St Hugh's - from which she received her degree in English Letters in 1927." Because she earned only a Second Class Honours degree, she did not attempt an academic career, but chose instead to accept the first job which was offered to her - a teaching position in a private boarding school for girls. She did not find the job to her liking, however, and left after only one term. Over the next three years she worked at a succession of temporary jobs, which reportedly included doing social work among London prostitutes. Then, in 1931, she assumed the ownership of a small secretarial agency in London - Murrells Typewriting Bureau - which was located in a basement office at 49 Victoria Street... Eileen gave up the typing bureau when she decided to pursue a degree in psychology. She was encouraged in this ambition by her brother, whom she assisted in her spare time by editing and typing his scientific papers....

From 1933 to 1935 Laurence was Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons and was at the forefront of research on heart disease and tuberculosis. In 1936 he founded a clinic at Lambeth Hospital for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, and also became the consultant surgeon to the Preston Hall tuberculosis sanatorium - which was an advanced centre of research and treatment operated by the British Legion. He gave lectures on his work to scientists in France, Germany and the United States, and he was co-author of two influential textbooks - Thoracic Surgery (1937) and Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Pathology, Diagnosis, Management and Prevention (1938). The astonishing thing about all this work is that it was done before he was forty. Of course, the fact that Eileen's brother was one of Britain's leading experts on tuberculosis was of no small interest to Orwell, and in the future Dr. O'Shaughnessy had in important part to play in Orwell's life."

[end quoting from Orwell The Authorzied Biography by Shelden]

So that sets the scene for March 1938 when Orwell had to be rushed by ambulance from Wallington in Hertfordshire to Preston Hall in Kent, thirty miles south of the outskirts of London - an all-day trip for Eileen to go visit him in the ensuing months - in between looking after everything alone at home.

Here's an excerpt from INSIDE GEORGE ORWELL by Gordon Bowker describing Orwell's medical condition:

"...Just before Homage to Catalonia appeared, after a week in bed with bronchitis, he began coughing up blood. It was extremely frightening for Eileen, who later wrote to Jack Common, 'The bleeding seemed prepared to go on for ever & on Sunday everyone agreed that Eric must be taken somewhere where really active steps could be taken if necessary - artificial pneumothorax to stop the blood or transfusion to replace it...' Laurence O'Shaughnessy saw him transferred immediately by ambulance to Preston Hall Village, a British Legion sanatorium, near Maidstone in Kent, where he was consultant thoracic surgeon. He was admitted on 17 March, 1938. Since childhood, hospitals had held a peculiar dread for him and he grumbled to Eileen about being sent to 'an institution devised for murder'. But the fact that he was in the care of a doctor he knew clearly helped. Not only that, but he was put in a private room paid for by Laurence."

"Hard work and neglect had taken their toll. Since returning from Spain, in addition to writing his book he had produced four articles, twelve reviews and several letters for publication. He was clearly exhausted, but still refusing to admit his wretched condition. Although no tubercle bacilli were found in his sputum, further tests told a rather different story, as his medical record reveals. The doctors found 'heavy mottling over the lower lobe of the left lung, with nonspecific fibrosis of the right lung', and he was treated with injections of vitamin D. However, at the conclusion of their tests the doctors drew a darker conclusion, and a postscript to his report reads 'T.B. confirmed'."

"Even though, finally, he had to face up to the bad news, he still tried to play it down, writing to a friend, 'I am afraid from what they say it is TB all right but evidently a very old lesion and not serious.' Two weeks later, writing to another friend, the old complacent Orwell had returned, denying the cruel reality of his broken health. 'I am much better,' he wrote, 'in fact I really doubt whether there is anything wrong with me.' (Years later, clearly diagnosed as having full-blown tuberculosis, he blamed it on the freezing Spanish winter he had spent shivering and coughing in the trenches on the Aragon front. But he could have acquired it at any time in his life - as a child, out in Burma, among tramps, even in a Paris hospital.)"

"He was ordered to rest and refrain even from 'literary research' for three months. It was particularly galling for Orwell, who already had another novel in mind...He was to remain at the sanatorium for five and a half months, by which time he had gained nine pounds. That summer it was decided that he needed to go abroad, 'somewhere south' to convalesce for the coming winter...Laurence suggested Morocco which, according to a French colleague, would be both equable and dry, the perfect place for a man in his condition..."

[end quoting from Inside George Orwell by Bowker]

Now here's how Michael Shelden describes it in ORWELL THE AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY:

One report on his medical condition at Preston Hall indicates very plainly why he was not released earlier, and gives some insight into the overall state of his health:

"In view of the history of recurrent haemoptysis, the condition was considered to be tubercular, and the heavy mottling over the lower lobe of the left lung was thought to be due to a post-haemoptoeic spread of the disease. But as there was also a history of 4 attacks of pneumonia, and since a bronchiectatic dilation could be recognized on the left lower lobe, a primary condition of bronchiectasis (and not tuberculosis) was considered possible. Until Pulmonary Tuberculosis could be definitely excluded, he was treated as suffering from the condition, and was kept strictly at rest, and given a course of colloidal calcium injections intramuscularly, with Vitamin D."

As the consultant surgeon at the sanatorium, Laurence O'Shaughnessy visited Orwell once each week and made every effort to determine whether his brother-in-law was, in fact, suffering from tuberculosis. Dr Arnold Bentley, the physician who preserved Orwell's file at Preston Hall, and who made it available for this biography, believed that 'quite searching and for the time adequate investigations' were made at Preston Hall to detect any sign of tubercle bacilli in Orwell's lungs. If Dr O'Shaughnessy could not make the diagnosis, then it is doubtful that any other lung specialist of the time could have proved otherwise. At the very time that he was attending his brother-in-law, the doctor was in the middle of writing, with two other men, an authoritative textbook on the disease.

In the meantime, there was not much that could be done for him. He was given injections of vitamins and minerals and was kept on a healthy diet, which produced a modest weight gain of almost ten pounds. And he was forced to spend a great deal of time resting in bed. When he tried to combine this with long periods of writing, he was rebuked. His medical records contain a notation stating that the doctors had 'warned him of the risks of literary research'. He complained to his friend Jack Common, 'The bore is I can't work...I am studying botany in a very elementary way, otherwise, mainly doing crossword puzzles."

Preston Hall was a progressive place with a first-rate staff and pleasant surroundings. The main part of the hospital was housed in an enormous country house built in 1849 by a railway millionaire. The house stands on a hill overlooking the Medway valley, near the little town of Aylesford. In Orwell's time the grounds were spacious and immaculately maintained. There were rose gardens, and a long avenue of tall cedars. The British Legion had purchased the estate in 1925 with the aim of making it a model sanatorium for ex-service men. Orwell was one of the few patients at the institution who had not been in the Army or Navy, but as the brother-in-law of the consultant surgeon, he was fortunate enough to be admitted on a special basis. In addition, he was given a private room. All in all, it was a comfortable arrangement for him, and after he had been there for a week or two, he did admit that it was 'a very nice place'.

[end quoting from Orwell The Authorized Biography by Shelden]

Now here's an excerpt from THE LOST ORWELL, by Peter Davison, describing Eileen's brother's career and work:

Dr Laurence Frederick O'Shaughnessy (1900-40), was born at Sunderland and left school aged 15 to do war work. He studied in coastguards' huts until he was old enough to read medicine at Newcastle Medical School, from which he graduated FRCS aged 21. In 1924 he joined the Sudan Medical Service and was in charge of the hospital at Omdurman for 7 years. During his leaves he visited Ferdinand Sauerbruch in Berlin and became interested in thoracic surgery. When he returned to England he received the first Royal College of Surgeons' research fellowship in order to investigate the blood supply to the heart in cardiac ischaemia and he developed surgical treatments for pulmonary tuberculosis. By April 1933 he was applying omental grafts and in 1936 successfully developed the technique on a 64-years-old heart patient. The following year he was awarded the Hunter Medal Trienniall Prize for research work in surgery of the thorax and in that same year his and Sauerbruch's Thoracic Surgery was published; it was the proofs of this book that Eileen was reading. As the account of his life (from which these notes are taken) in Stephen Westaby's Landmarks in Cardiac Surgery states, 'In a few years, O'Shaughnessy created a new outlook in cardiac surgery and did more to advance this subject than anyone in England, if not the world'. When war came in 1939, believing that chest wounds needed immediate treatment, he volunteered to serve at a casualty clearing station for the British Expeditionary Force in Flanders. He was killed by a stray bullet during the retreat to Dunkirk.

[end quoting from The Lost Orwell by Davison]

Toward the end of his stay at Preston Hall, Orwell was allowed to leave the building and walk the grounds - and, as you say, work at the Manor Farm. He also ventured out on day trips to the surrounding area.

In my reading about Preston Hall I learned about the Kit's Koty rocks (same time-period as those at Stonehenge) that are near the town of Ayelsford. They're the gravestones of Catigern, son of the British King Vortigern, who fought a battle there in 455 against the Anglo-Saxons Hengist and Horsa.

In August 1938, at Preston Hall, Orwell started a diary. He describes going to Kit's Koty, and even draws a diagram of the rocks.

Orwell's Diary, Preston Hall, Aug 21, 1938 (Yesterday fine & fairly warm. Went in afternoon and saw Kit's Coty, a druidical altar or something of the kind. It consists of four stones arranged more or less thus: The whole about 8' high & the stone on top approximately 8' square by something over a foot thick. This makes about 70 cubic feet of stone. A cubic yard (27 cubic feet) of coal is supposed to weigh 27 cwt., so the top stone if of coal would weigh about 3 1/2 tons. Probably more if I have estimated the dimensions rightly. The stones are on top of a high hill & it appears they belong to quite another part of the country.

An in another entry Orwell mentions Marx being with him on the drive leading out of the grounds.

Orwell's Diary, Preston Hall, Aug 9, 1938 (Caught a large snake in the herbaceous border beside the drive. About 2' 6" long, grey colour, black markings on belly but none on back except, on back of neck, a mark resembling an arrow head all down the back. Not certain whether an adder, as these I think usually have a sort of broad arrow mark all down the back. Did not care to handle it too recklessly, so only picked it up by extreme tip of tail. Held thus it could nearly turn far enough to bite my hand, but not quite. Marx interested at first, but after smelling it was frightened & ran away. The people here normally kill all snakes. As usual, the tongue referred to as "fangs".)

It was shortly before Orwell's discharge from Preston Hall on September 1, 1938. Perhaps your father had brought Marx to the grounds that day to be picked up by Orwell's sister from Bristol, Marjorie, who would be looking after the dog while Orwell and Eileen were in Morocco.

Although Orwell didn't want to go to Morocco - it costing time and money he couldn't afford - Eileen's brother insisted, and then an anonymous friend donated 300-pounds (which Orwell accepted as a loan and paid back in 1945 with earnings from ANIMAL FARM). He and Eileen set off as soon as he was discharged from Preston Hall. Dr O'Shaughnessy had prescribed the hot, dry climate of northwest Africa and, although it took awhile for them to aclimatize, it turned out to be good for Orwell's health.

He was able to rest there, uninterrupted by visitors and demands for his time as would have been the case if he'd stayed in England. During the six months they were there, Orwell gained weight and wrote COMING UP FOR AIR (symbolic of him taking a breather into the past, trying to escape the horror of the thought of the upcoming war, sentiments expressed through George Bowling, the main character of his book - and a personification of himself, as usual).

Orwell and Eileen got back to England in March 1939, and six months later England joined the war - siding with Stalin's Russia against Hitler's Germany. Nine months later, in June 1940*, Eileen's brother Laurence - disciple of Germany's world-renowned tuberculosis expert - was killed at Dunkirk.

Here's the effect of his death as described by Sheldon in ORWELL: THE AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY:

There was nothing anyone could do to comfort Eileen when she learned of her brother's fate. She went into a long period of deep depression which reportedly lasted many months and which led her to the verge of a nervous breakdown. Her friend Margaret Branch recalled that for a time Eileen could barely bring herself to speak to anyone. 'One saw in her the visible signs of depression. Her hair was unbrushed, her face and body thin. Reality was so awful for her that she withdrew - the effects lasted perhaps eighteen months. In her severe depression she was facing the dark night of the soul. Nobody could get through to her'. Lydia Jackson thought that 'Eileen's own grip on life, which had never been firm, loosened considerably after her brother's death.' Tragically, her suffering was made worse in 1941 when her mother died.

There was very little in Orwell's letters and diaries which would indicate that his wife was in such pain. He did not talk about such things to other people, and he would not have agonized over it even in his private diaries. There was no question that he felt her pain and was moved by it, but he took a stoical attitude towards such things, and was not prepared to deal with them in the open. He was always so careful to keep his emotions under control, at least on the outside, but no one can read very far in his works without realising that the passive expression which he was inclined to present to the outside world masked deeply felt passions....

Although he could not have anticipated it at the time, Orwell would later have his own personal reasons for regretting Dr O'Shaughnessy's early death. At the end of 1947, when Orwell was first diagnosed as having tuberculosis, he was treated with the latest drug - streptomycin - but there were other drugs in development, and other available treatments, all of which could have been employed to the maximum effect if his brother-in-law had lived and had been able to give him the full benefit of his expertise. This is not to suggest that Orwell was neglected in any way by the doctors who treated him in the late 1940s, but there is just the chance that O'Shaughnessy, who was such an active medical scientist, might have been able to do more for Orwell. By itself, streptomycin was not effective in Orwell's case - some forms of the disease were resistant to it - and the latest drug in 1949 - PAS (para-aminosalicylic acid) - also had mixed results when used on advanced cases like Orwell's. He received PAS, but there is no indicaton that any of his doctors tried a third treatment, the success of which was reported in the British Medical Journal only weeks before he died. This treatment involved a combination of the two leading drugs, and as one expert has noted, the report cited a study which 'demonstrated unequivocally that the combination of PAS and streptomycin prevented the development of streptomycin-resistant strains of the tubercle bacillus'.

Perhaps it is fruitless to speculate on what might have happened if O'Shaughnessy had lived, but rarely does one encounter such a strange working of fate in the interconnected lives of two distinguished men - one brother-in-law a writer who would die of tuberculosis, the other a leading chest specialist who died young on a battlefield where he had gone to learn more about his speciality. But, given the way that Orwell neglected his health, even Dr O'Shaughnessy might not have been able to save him.

[end quoting from Orwell The Authorized Biography by Sheldon]

Thanks again for sharing your Orwell at Preston Hall insights. It inspired this explanation of Laurence O'Shaughnessy's contribution toward the betterment of mankind - not least of which was his role in helping keep George Orwell alive.

All the best,

Jackie Jura

conversation continues at PRESTON HALL ORWELL ANIMAL FARM

*Reader Richard points out a mistake in the date of Dr O'Shaughnessy's death -- it was in May 1940, not June 1941. See ORWELL BROTHER-IN-LAW DIED AT DUNKIRK

Reader Jane is researching Orwell's connection to Preston Hall as inspiration for "Animal Farm"

WALLINGTON WILLINGDON ANIMAL FARM

VISITING ORWELL'S WALLINGTON FARM

Jackie Jura

~ an independent researcher monitoring local, national and international events ~

email: orwelltoday@gmail.com

HOME PAGE

website: www.orwelltoday.com