"I live one minute at a time.

If I started thinking I'd have to ask for asylum abroad.

Galileo was condemned for saying the earth went around the sun.

That's just what it's like here:

anyone who wants to change anything is finished."

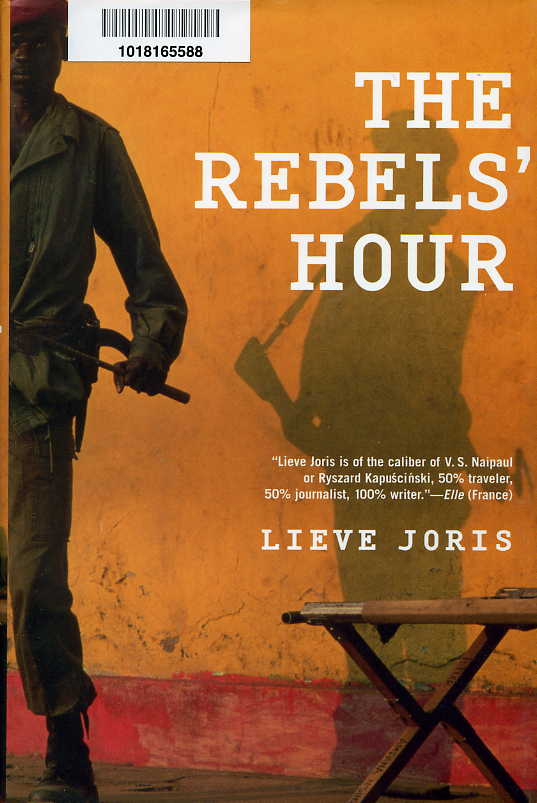

DID NKUNDA READ REBEL'S HOUR?

"No one who tries to do any good can survive here.

You can't think logically in a land of barbarians."

To Orwell Today,

re: NKUNDA HERO IN REBEL BOOK

Jackie,

Hi! I have just read the Rebel Hour book translated in french. Yesterday I found it at the public library and read it the whole afternoon until midnight.

It is actually the real story about how the 2 first wars in Congo were conducted, with some of the details I have heard from soldiers who fought them. To the exception of ASSANI himself, the rest are real names of people who made the events. It gives exactly the background of everything. ASSANI is from the South; the Banyamulenge people, the way their life is and history, is accurate; how they got caught in this whole playgame - it is exact. Interestingly the story is also leading or tacitly predicting what is happening now.

I am definitely sure that our friends in Kigali will not like the book because it is putting out in the open what has been happening. Don't wonder why nobody talked about it. I wish I could have read it before the Chairman was arrested. I would have sent it to him.

-Sharangabo Rufagari

Greetings Sharangabo,

I'm so glad you finally got around to reading THE REBELS' HOUR - I've been hoping you would ever since I posted NKUNDA HERO IN REBEL BOOK this past February 2009 - which is when I read it (which was a month after Nkunda was arrested).

The whole time I was reading it I was wondering if Nkunda had read it and what he would have thought about it.

Then - in March - I came across AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR, LIEVE JORIS, where she's asked that very question.

Below is the excerpt from the interview. It begins about half way through, at minute 33:35:

Now your novel has been translated into French, as well, which means that the main character of the novel can actually read the book. Can you maybe tell us something about his reaction to the book.

Well I must say that this man isn't called Assani in reality. I have had to protect him and I've tried to disguise him a little bit. And of course he recognizes himself 100% because it's a picture that's a little bit different, but not so much....

The three of us solved the problem of publishing this book as it came out because in the beginning Assani was panicking. I went to Congo last year for five weeks. And he was somewhere. And I was somewhere. And meanwhile he was reading. And we were sometimes communicating by mobile phone.

And one day he called me - he was on page 90 or something - and he said:

"So you want to kill me. And who is going to take care of my wife and children after that?"

And even though it scared me a little, I said:

"Just finish reading the book first".

And then, of course, he called me - at two thirds - and was...ummm. At the end he said:

"I have to drink this cup".

And he was courageous....

This book is very early. It's early because the things are still happening and the truth is not totally out; the cards are not really on the table. And it was difficult from time to time to write at this moment.... [end quoting from The Rebels' Hour]

All the best,

Jackie Jura

PS - Did you notice that the reason the author named the book THE REBELS' HOUR is because that's what she used to call the time of the day when she'd interview Assani on the mobile phone - where he'd be calling anytime, anywhere, from somewhere in the bush.

Below is an excerpt from the book, along those lines. It's a conversation between Assani and his friend Claudine - the white Belgian woman who owns the bar/restaurant in Lubumbashi (where Assani first met her in 1997 while a battalion commander in Katanga province fighting Rwandan Hutus and Congolese Mai Mai on the way to overthrowing Mobutu in 1998) and they've since become friends. In my reading of the book I consider the character of Claudine to be the voice of the author, Lieve Joris, just as I consider the character of Assani to be the voice of Nkunda. In this conversation, time period 1998, Assani is in Eastern Congo and Claudine is on vacation in Belgium (where the author Joris grew up and lived while she wrote the book):

...He tapped Claudine's number. "Allo?"

It was good to hear her voice. When he phoned her in Lubumbashi she'd sometimes sounded nervous -- in Belgium she could speak more freely.

"You feeling better?" she asked.

"Who told you I wasn't feeling well?

"You did!"

"Sorry, I'm still overworked, I think."

He could hear her waiting for him to go on.

"This war is far more difficult than the first war," he sighed. "Everyone's against everyone else. How can I relax in a situation like this? I look death in the eye every day. Even right now, talking to you."

"You should get away for a bit. Doesn't a soldier have a right to a holiday?"

He laughed at the thought.

"No, no, not yet. I live one minute at a time. If I started thinking I'd have to ask for asylum abroad. Galileo was condemned for saying the earth went around the sun. That's just what it's like here: anyone who wants to change anything is finished."

He had no idea whether she understood any of this, but at least she was listening. And she wouldn't hold what he said today against him tomorrow.

"I reckon you need a rest," she said.

"I'll rest when I'm old - but a man like me doesn't live to be old."

"Why shouldn't you live to be old?"

"Because pretty soon they'll shoot me."

"Why?"

"First because I'm an African, second because I'm a Congolese, third because I'm a Tutsi, and on top of that . . ." -- he let out a high-pitched, joyless laugh -- "a Munyamulenge!"

At the other end a tense silence fell. No harm frightening her, he thought -- give her a sense of how it feels to be in a godforsaken town like Kalemie with no idea whether or not you'll make it through the night.

"No one who tries to do any good can survive here," he said. "You can't think logically in a land of barbarians."

"You used to believe in what you did," she said hesitantly. "What happened? What's changed?"

"No one wants us here. We still have weapons, but when supplies run out we'll have to flee. Fortunately I've got a pistol. The last bullet is for myself; they won't throw a burning tire round my neck like they did with the Tutsi in Kinshasa."

"Where are you?" she asked, worried.

"Somewhere in the east," he said reluctantly. "Not far from Uvira."

"How come you're alone?"

"The others went out."

He looked around.

"Do you want me to describe the room I'm in?"

He didn't wait for an answer.

"On the table in front of me are two pistols, a walkie-talkie, and, wait a moment . . . " -- he pushed some papers aside -- "Two chargers and a box of bullets. Against the wall is my rucksack, plus a Kalashnikov, a grenade launcher . . ." [end quoting from THE REBELS' HOUR]

...conversation continues at ASSANI ESSENCE OF NKUNDA

Jackie Jura

~ an independent researcher monitoring local, national and international events ~

email: orwelltoday@gmail.com

HOME PAGE

website: www.orwelltoday.com