He was defiant: he'd fought against Mobutu,

but the revolution he'd hoped for had failed to materialize.

He told me Kabila had turned his back on the rebels who'd helped him to power

and surrounded himself with people from Katanga, his home region.

He believed the regime was heading for a tremendous crash.

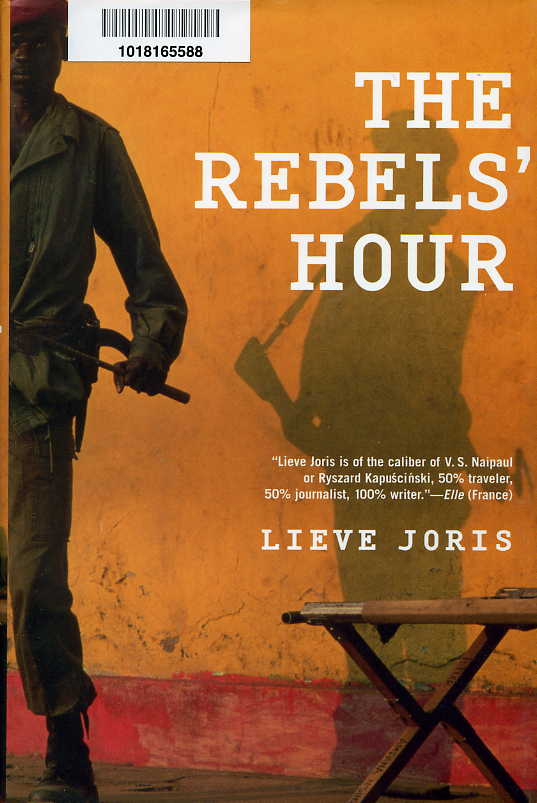

NKUNDA HERO IN REBEL BOOK

I thought he'd been killed, but some time later he suddenly reemerged,

at the end of a crackling satellite line.

He was in the forest, in the east of the country, where a new rebellion had broken out;

I could hear the shrieking of wild parrots in the background.

"Are you still a writer?" he asked. "Well, now you have a story."

I've mentioned elsewhere on "Orwell Today" that books tend to jump off the shelves and into my arms - as if by magnetic pull - even though I know nothing about their particular existence until that time - but about which their subject matter is one of affinity to my mind, heart and research.

I won't go into the details of how the latest book (scanned above) jumped into my arms (except to say my husband discovered it in the library yesterday when returning another book about the Congo - excerpts of which I shared in NKUNDA RIGHT ON CHINA WRONGS - and brought it home to me). It couldn't have come at a more opportune time, its subject matter being a thinly-veiled biography (in a non-fiction novel) of a person I've been writing a great deal about lately - General Laurent Nkunda. See articles under KNOW NKUNDA CONGO

As a matter of fact, I had just the day before put an article on the website entitled IS NKUNDA REFS UNPERSON? because it was the one-month anniversary of the day Nkunda had disappeared from the Congo and hadn't been seen or heard from since (by any journalist in the world).

This new book - coming as it did at this time - is symbolic communication from Nkunda himself because it was written by someone attempting to explain the enigma of Nkunda (although she gives him a fictitious name and changes a few - very few - other details). But to anyone with understanding about Congo, Rwanda, Kabila, Kagame et al (who are all mentioned by real name) the hero of her book (who she names Assani) is without a doubt Nkunda.

The author states in her preface that she isn't a supporter of his cause. But that didn't stop her from representing him honestly to those who are - and to those who will be after reading her passionate, historically accurate portrayal of Nkunda's role in Congo.

The time frame of the book ends in 2004 with Nkunda (Assani) - now a general in Kabila's army in Kinshasa in the west - teetering on the verge of quitting to join rebels in the east who are clamouring for him to come back to Kivu to help them fight against the Rwandan Hutus and Congolese Mai Mai who are attacking them under the noses (and with help from) thousands of United Nations and Kabila troops stationed there.

The next book on Nkunda (whoever writes it) will have to pick up where this one leaves off - ie filling in the years from 2004 to present-day and beyond into the future that - hopefully - includes Nkunda back in Congo winning the battle for peace and prosperity for his people - ALL the people of the Congo. It's living, breathing history in the making. ~ Jackie Jura

NKUNDA LAST CONGO INTERVIEW 2009

NKUNDA PILGRIMAGE RECONCILIATION 2006

THE REBELS' HOUR

by Lieve Joris, published 2006

(translated from Dutch into English, 2008)

excerpt from preface:

In May 1998, in the Congolese mining town of Lubumbashi, I met the soldier who was to become the model for Assani, the main character in this book. He was a Tutsi rebel who'd arrived from the east of the country with Mzee - "Old" - Kabila to overthrow the dictatorial Mobutu regime. He belonged to the Banyamulenge, a people living in the inhospitable high plains of eastern Congo, close to Rwanda and Burundi. As a child Assani had herded cattle. Later he gave up his studies to become a rebel. A herdsman turned soldier: I could immediately see the outline of his life story.

The Banyamulenge originally came from Rwanda. They had a reputation for being belligerent, violent, and secretive. Along with the Rwandans they'd helped Kabila to power, but they were distrusted by many Congolese. There were rumors that Kabila wanted to rid himself of them and their Rwandan allies.

It was not my first trip to Congo. In the 1980s I'd spent six months traveling through what was then still called Zaire, in the footsteps of an uncle who'd been a missionary in the period when Congo was a Belgian colony. I'd experienced the Mobutu era at close quarters and written a book about it.

In the years since then Mobutu had taken his country, one of the richest in Africa, to the brink of bankruptcy. State institutions had survived in name only and an army of unpaid soldiers was terrorizing the population. By the time the rebels led by Mzee Kabila began advancing from the east in 1996, the regime was so rotten that it fell within seven months.

I'd flown to the capital, Kinshasa, in May 1997 and spent a year traveling in the country that Kabila had re-named Congo; I was working on a second book. Many people hoped the fragile peace Kabila had brought would hold, that after thirty-two years of Mobutu followed by a turbulent takeover the Congolese would be granted tranquility at last. Meeting Assani made me realize we were deluding ourselves. He was defiant: he'd fought against Mobutu, but the revolution he'd hoped for had failed to materialize. Assani told me Kabila had turned his back on the rebels who'd helped him to power and surrounded himself with people from Katanga, his home region. He believed the regime was heading for a tremendous crash.

His style of driving, the things he said, the way he moved - in the middle of the city I was suddenly in the bush. Beneath his hard, closed-off exterior Assani seemed vulnerable, ready to tell his story. I must follow him, I thought; by following him I'll get to know what's going on behind the scenes.

Assani's predictions proved accurate. A few months later he was in Kinshasa when Kabila ordered his Rwandan allies to leave. All Tutsi were associated with them, and in the streets of the capital they were hounded, lynched, and burned. I sat and watched it all on television. Assani was tall and slender -- unmistakably a Tutsi. I couldn't imagine him surviving this. Something he'd said during our last telephone conversation still reverberated: "You don't know even a hundredth of what's happening here. We're soldiers, but we're being forced to engage in politics."

I thought he'd been killed, but some time later he suddenly reemerged, at the end of a crackling satellite line. He was in the forest, in the east of the country, where a new rebellion had broken out; I could hear the shrieking of wild parrots in the background. "Are you still a writer?" he asked. "Well, now you have a story."

In the years that followed I tracked my subject and slowly crept inside. The rebels controlled the eastern half of the country but had failed to win over the local population. They were supported by the Tutsi regime in Rwanda, regarded by the Congolese as an occupying force. Pockets of resistance by the Mai Mai -- a people's militia - were everywhere, despite repeated and heavy-handed attempts to crush them.

Meanwhile Assani was rising to become one of the most important soldiers in the rebel movement. I met him in the rebel capital, Goma, in a fortress where he lived with forty child soldiers. I saw him in the equatorial town of Kisangani, bivouacked in a hotel room with a closet full of munitions. I visited him in his native province, South Kivu, where Banyamulenge soldiers had started a revolt; he was fighting the very people he'd chosen to defend.

But just as often I didn't see him at all: he would go off on a mission without leaving any clues to his whereabouts, or spend several months at the front. One time I came on him at an airport in the interior; he gave no sign of recognition.

His disappearance shortly after our first meeting had alarmed me. What if he was killed? I couldn't rely solely on him. I explored his environment, met his fellow rebels, his mother, and uncle, a fellow student, a former girlfriend. Although some of them were no less suspicious than he was, things they let slip now and then helped me to understand what a complicated life Assani led, what difficult choices he had to make.

I who had grown up in antimilitaristic times suddenly found myself sitting next to rebels with crackling walkie-talkies in a jeep that smelled of gasoline, young soldiers in the back, or in a house they'd seized, where a painting hanging lopsidedly on the wall was the only reminder of civilian life. My new acquaintances wore a medley of uniforms and tended to talk among themselves in a language I didn't understand, stop answering the phone from one day to the next, or vanish without a trace.

For their part, they thought me an odd customer. They didn't know anything about writing -- except for security service reports; they were familiar with those. I must surely be an agent; otherwise, who was paying my travel expenses? Who was financing the endless hanging about I subjected myself to?

It wasn't easy to get inside, but once there I soon saw nothing else. Back home in Amsterdam, I looked in amazement at children in the streets dressed in fashionable camouflage clothing, at boats decommissioned by the Dutch navy that puttered past my window as pleasure craft.

For days on end I scoured Web sites, peering at weaponry, and felt strangely drawn to army surplus stores. They smelled of war and were full of handy bits of gear my new acquaintances in the bush could do with: floppy hats with mosquito netting hanging from the brims, a flat thing made of fabric that folded out to form a basin, earplugs the Americans used in Vietnam to dampen the noise of helicopters and mortar fire.

Assani's forebears had come from Rwanda in the nineteenth century, along with their cows. Growing up in the high plains of South Kivu he'd barely been aware of his origins, but at school in the valley he learned he was a Tutsi. It was a loaded term in those days; in Rwanda a bloody power struggle between Hutu and Tutsi was under way that would lead to genocide in which 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu were killed.

When the Rwandan war spread to eastern Congo and the Mobutu regime chose to side with the Hutu, Assani increasingly found himself with his back to the wall, until his identity no longer coincided with that of his country but instead with that of his people, and he crossed the border into Rwanda, where a pro-Tutsi regime was about to take power.

I traced Assani's route. Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi -- I ranged across the countries of the Great Lakes region that had become involved in the Congolese war, and visited the campus where he'd been studying when he set out one evening to go to war against Mobutu.

I finally managed to travel to Assani's native region in the high plans of South Kivu in the spring of 2004. There I became aware of the hurt he'd suffered as a child and how it had made him a loner. There I understood why he'd left the high plains and would never return, why the place he came from no longer afforded him any protection, and why the new world he found himself in was just as inhospitable.

All that time Assani thought he was going to die, but he survived. In 2001 Mzee Kabila was assassinated by a bodyguard from the east. Mzee's son Joseph succeeded him, paving the way for peace negotiations that would lead to national reunification. In 2003 Assani, now a general in the reunited national army, arrived in the capital he'd fled five years before in fear of his life.

The story I wanted to write about Assani was probably not the one he had in mind. I wasn't a supporter of his cause; I wanted to understand what had made him. The contact between us was not always easy, but a mutual curiosity kept us going. No matter how intractable, suspicious, and impenetrable he could be, he felt a need to talk about the world in which he'd ended up.

In the fall of 2004, more than six years after I first met Assani, I returned to Amsterdam with the material for this book. I'd done all I could to gain an insight into Assani's life, but certain periods remained mysterious. How exactly had he become a soldier? Where did his true loyalty lie? To what extent had he been involved in the massacres perpetrated by the rebels in the east?

These were questions Assani had not been prepared to answer. He was still keeping some cards hidden. He and his fellow soldiers were inclined to obfuscate their lives, throwing up one smokescreen after another. Sometimes I had the impression that every time a fellow rebel died, they held his story up to the light and appropriated whatever suited them. How could I write a book about people who were so engaged in self-mythology?

To tell the story I'd watched unfold in the shadows, I had to venture deeper into the subterranean depths of my characters than I'd ever done before. Only after I withdrew behind the walls of a monastery near the Belgian city of Bruges did the material finally yield itself up.

The facts in this book have all been researched in minute detail. But in order to paint a realistic picture of my characters, I've had to fill in some parts of their lives from my own imagination. It was the only way to make the story both particular and general.

More than forty years after independence, the concept of the nation-state is fading fast in many African countries. The continent is littered with tribalistic armies that sustain themselves by looting and extortion. War has become their profession; peace only exposes their shortcomings. The Great Lakes region is one such area. The wars that have raged there since the early 1990s have cost several million lives.

Through Assani I was able to desribe this reality. He went to war to defend his people, killed and saw friends killed. Somewhere along the line he lost sight of how it had all started and where it was all leading. Peace negotiations brought him to the capital, but as long as the problems in his native region remain unresolved, the thread that connects him to his country will be extremely fragile....[end of preface to The Rebels' Hour, by Lieve Joris]

DID NKUNDA READ REBEL'S HOUR? and ASSANI ESSENCE OF NKUNDA

Jackie Jura

~ an independent researcher monitoring local, national and international events ~

email: orwelltoday@gmail.com

HOME PAGE

website: www.orwelltoday.com