China had swooped into Katanga and begun hauling out commodities at enormous rates,

pushing the price of copper to three dollars a pound and cobalt to thirty - the highest in a decade.

China's demand for cobalt rose tenfold from 1997 to 2005,

when up to 90 percent of China's imported concentrates and ores were coming from Congo.

NKUNDA RIGHT ON CHINA WRONGS

In Katanga, the ore was smuggled out in the dark of night,

across the border in beds of covered trucks and railcars, past the eyes of police

who hadn't been paid in months and so were hard-pressed to refuse the hush money.

It went down through Zambia, Tanzania, and South Africa, where it was processed,

then put into giant containers and shipped east into Asia.

As I've been following events in the Congo - particularly this past two and a half years since I travelled there - I've been alarmed by how Communist China is taking over there - as they've also done elsewhere in Africa to the detriment of every nation where their "footprint" is felt.

The international media (the Orwellian Ministry of Truth/Lies) which is owned by elite corporations with people like Kissinger on their boards of directors - conspire in a cover-up of silence over China's evil doings in Africa. Occassionally there'll be an article about China's genocides in Sudan and Zimbabwe - to name just a couple - but these are few and far between. See articles listed under the section CHINA OILS SUDAN GENOCIDE and MUGABE HAS YELLOW FEVER and AFRICA SILK ROAD TO CHINA and CHINA PUTS ON AFRICAN MASK for examples of African countries where China is pillaging their valuable resources.

You'd think that nations of the Western World would be opposed to China taking over in Africa where - to varying degrees - we've invested billions in infrastructure and development over the past couple hundred years - only to have it all now handed over (in neglected state but reparable) to Communist China.

But then, when a person realizes that the governments of the Western World - especially United States, Canada and Australia - are also handing our resources over to Communist/Capitalist China and Russia - it becomes obvious that they're in bed together and we - the citizens of all continents - are being screwed. It's what Orwell described in "1984" as the three super-states, ie Russia, America/UK and China all "propping one another up like three sheaves of corn" setting up systems under the rule of Goldstein, the BIG BROTHER of all little brothers. See CHINESE TAKE-OVER and GOLDSTEIN CONSPIRACY IN 1984

But getting back to the Congo - a place dear to my heart in the heart of Africa - where the only human being standing up for his country against China's takeover of its resources is Laurent Nkunda. See CONGO RICHES CHINA NOW and CONGO 500-POUND GORILLA CHINA and NKUNDA SAY CONGO OWNS RESOURCES.

Because of his stand against China in Congo, Nkunda is being demonized in the world press and persecuted by governments in the Western World who are accusing HIM of atrocities (committed by the forces he's fighting AGAINST) and cutting off aid to the only African country that defended him, ie little Rwanda where 1 million people were hacked to death 14 years ago (with machetes made in China) and from where the genocidal maniacs Nkunda is fighting originated. See RWANDA GENOCIDE HORROR and KABILA KILLS, RAPES & BLAMES NKUNDA

Under pressure from all sides - ie the Capitalist World and the Communist World and Goldstein's World Bank and International Monetary Fund - Rwanda did a dastardly deed - they kidnapped Congo's only protector - Laurent Nkunda - and have him hidden away somewhere where he can't do any more good to help his people.

Laurent Nkunda arrested in Rwanda. London Guardian, Jan 23, 2009. See KAGAME HELPING NKUNDA NOT

Further proof that the Western World is in cahoots with China is how the Western media (and the Chinese media) are saying that Nkunda and Rwanda weren't really interested in saving people from massacre by Hutus and their allies (the Mai Mai, Kabila army, and UN army) but are only interested in exploiting Kivu's (Nkunda's area of Congo) mineral resources. (Note in the following article there's no mention of China exploiting resources):

Rwanda goals in Congo under scrutiny. Institue War & Peace, Feb 13, 2009 (People in eastern DRC suspect Rwanda’s real motive for intervening in the region is to exploit natural resources....Meanwhile, DRC is happy with Nkunda’s arrest and soon hopes to have him extradited where he could be put on trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity relating to events in Bukavu in 2004 and perhaps more recently in Kiwanja in 2008. He has denied these accusations. Some Congolese believe Nkunda’s arrest is merely a distraction, meant to conceal Rwanda’s hidden agenda to exploit minerals. It is similar to events in 1996 when the Congolese were focused on the departure of former president Mobutu Sese Seko after 32 years of dictatorship. Anxious for a new regime, many Congolese didn't suspect that Rwanda's backing of Laurent Kabila in the war that toppled Mobutu would leave it in control of the resource-rich Kivu region....)

However, the fact of the matter is that the only natural resources North Kivu has is GORILLAS, and all South Kivu has is coltan and casserite - neither in the big league when it comes to PRECIOUS resources like copper and cobalt down in mineral-rich Katanga province where the Chinese are silently raping the land.

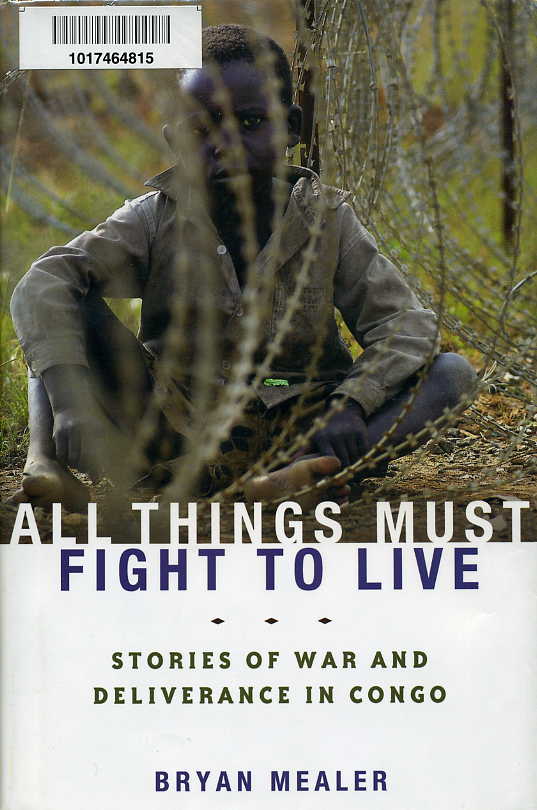

This fact about China's role in taking over Western and Congolese interests there was described very well in a book I read just last week entitled ALL THINGS MUST FIGHT TO LIVE: STORIES OF WAR AND DELIVERANCE IN CONGO, by Bryan Mealer.

The book is written by a one-time Associated Press reporter who spent three years in Congo reporting mainly from the Orientale province north of the Kivu area of the country where the Ugandan Lord's Resistance Army (the equivalent in terror and atrocities to the Rwandan Hutu and Congolese Mai Mai that Nkunda is fighting in his area of North Kivu) have reigned supreme since they were forced out of Uganda (similar to how the Hutu FDLR was forced out of Rwanda).

The book's exposure of China's resource-robbing of the Congo was just a very small part of what the author was writing about, which was mainly his observations of the humanitarian suffering inflicted by the LRA/Hutu/Mai-Mai etc and also his experiences - during time-off - of travelling up the Congo River from Kinshasa (once Leopoldville) to Kisangani (once Stanleyville) and later by train in Katanga from Lubumbashi (once Elizabethville) to Kalemi on Lake Tanganyika (across from where Livingstone once set up camp and Speke set out to discover the source of the Nile, ie Lake Victoria).

The author's interpretations about who are the bad guys and who are the good guys in the Congo are the opposite of mine. For example, he blames Nkunda and Rwanda for the post Rwanda-genocide wars in the Kivu area - instead of looking at them as the only forces fighting the negative forces there, ie Mobutu's - then Kabila's - army in alliance with Hutus and Mai-Mai who otherwise would be left to their raping, rampaging, and massacring of Tutsi and other tribes in those Kivu areas. See GOMA CAMP MAFIA HOTEL

However, I could relate to the author's irresistable pull to keep returning to the Congo - it being in his blood since the first time he went there - because I am also drawn to return there and was hoping to do so - but to a Congo that was free and prosperous and in the hands of Congolese - like how Nkunda wanted it to be. With Nkunda gone - and the Chinese in - I don't plan to travel there now.

The author and I were actually in the Congo at the same time - and even in the same area around Goma - in 2006 in the lead-up to the first national elections since Lumumba was elected back in 1960. I followed those elections very closely from back at home in Canada and was mesmerized in the parts of the book where the author describes election day in Kinshasa - with the resultant crack-down by Kabila when his opponent, Bemba, won enough votes to come to power (similar to what happened to Tsvangirai in Zimbabwe when he beat Mugabe). See GOMA LUMUMBA VOLCANO

I could also relate to the author's description of how the Congolese people feel about the Chinese in their country because I got the same reaction from every-day people when I was in Ethiopia (on my way home from Rwanda/Congo) - even down to the author's story of his converstaion with a Chinese businessman in Lubumbashi. I had a similar conversation with one in Addis Ababa where he was bragging about travelling all over Africa making lots of money - and he even gave me some yuan. See OUT OF AFRICA and CANADA GATE FOR CHINA

I could also relate to the author's reaction to the news (after returning home to the USA) that the Kabila government had signed a deal with China allowing it mining concessions in Congo (in exchange for a $9-billion LOAN to repair existing railway tracks built by Western World ingenuity and manpower a hundred years ago, and highways, hospitals, schools etc). The author thought it was an incredible deal (and approved) whereas I also thought it was an incredible deal (but, like Nkunda, I disapprove).

China in the Congo. Financial Times, Feb 9, 2009

The China-Congo deal provided for $9bn of Chinese investment in roads, railways, schools and clinics and in the rehabilitation of the mining sector. In return, Congo would cede majority rights in a joint venture to develop copper and cobalt concessions. Any difference that might emerge between the cost of infrastructure and revenues from the mines would be underwritten by the Congolese state. For the Chinese it was a classic win-win scenario..... Congo is saddled with $10bn of external debt stored up from the days of Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator. It has little to show for it, and certainly no roads or schools. This was money used to appease a cold war ally long after it became clear President Mobutu was stashing it in Swiss banks. Yet Congo’s western creditors are reluctant to write it off only to see new debt contracted to China on commercial terms.... Yet the bill for continuing state failure will land in Europe, not Beijing.

In actuality, it was Nkunda's outspoken condmentaion of Congo making this deal with China - and his demand that Kabila cancel the contract - that resulted - in my opinion - in Nkunda being removed from the Congo where he was becoming powerful enough to be legitimate opposition to Kabila and China. And so, like what happens to all voices of opposition in Africa - he was arrested and imprisoned and for all we know is being tortured or brainwashed into submission before being handed over to the government of Congo or some United Nations kangaroo court, as have all opposition members before him, including Lumumba in 1961 and Bemba in 2008. See CONGO IS LUMUMBA LAND and NKUNDA SAFE LIKE LUMUMBA?

In any event, that sets the background for the excerpts from the book that I'd like to share with "Orwell Today" readers regarding the author's description of the Chinese presence in Congo and how, like Nkunda, the Congolese people long for the day the white man was there developing their resources and building hospitals, schools, roads and railways and providing them with jobs - all of which - since Mobutu and Kabila took power - are gone or in ruins. ~ Jackie Jura

All Things Must Fight To Live: Stories of War and Deliverance in Congo

by Bryan Mealer

excerpts from pages 223-293:

...Katanga was the largest province in all of Congo, stretching south to Zambia and east to Tanzania, which lay just across Lake Tanganyika. Here the rain forests thinned as the elevation rose, the siphoning jungle giving way to open savanna and cool breezes. Here the melodic Swahili of the east replaced the sharp Lingala of the west, and the people themselves seemed to mellow as the air became lighter. Even the beer tasted better in Katanga. But it wasn't just the high altitude that made it different, though it reached sixty-five hundred feet in places. Nor was it the crisp breezes that whipped into the lower valleys, creating a force field against the swampy jungles in the north.

It was money, almost an endless supply of it thanks to one of the largest and purest deposits of cobalt and copper in the world. So much copper was bulging under the surface in Katanga that the earth actually glowed from space.

The mining industry certainly gave the people of Katanga a sense of pride, especially when comparing themselves to their fellow countrymen. But as in Ituri, the minerals carried with them a curse locked inside the blessing. While the minerals made the province a titan in central Africa, they'd also sparked bloody secession attempts and sucked the UN into its first enterprise in Congo back in 1960. Even now, the minerals continue to drive the wholesale pillage of the province by foreigners and corrupt state officials....

The red dirt, it turned out, was also filled with cobalt, tin, diamonds, coal, silver, magnesium, uranium, and other minerals in huge demand as nations built themselves for the industrial age. Even more than rubber, the mines brought wealth to the colony, built the European-style cities that sprouted along the southern savanna, with the largest and proudest of them being Elizabethville, or modern Lubumbashi. The mines finance the hospitals and roads that set the Belgian Congo apart from other colonies and gave jobs and pensions to thousands of Congolese. As a result, Katangese were healthier and better educated and also more worldly, as the mines also attracted Africans from elsewhere in the continent, in addition to one of the largest populations of Europeans in central Africa....

So much of the country's history had played out in Katanga, collected in that bottom crevice and pushed into the heart by all the money buried in the dirt. William Stairs's murderous expedition into Msiri's kingdom undoubtedly secured the vast mineral fields for the cause of Western civilization. But the droves of fever-driven men couldn't have moved an ounce of copper until another crucial milestone was passed: September 27, 1910 - the day the Chemin de Fer du Katanga, or Katanga Railway, finally rolled into Lubumbashi. If the copper gave birth to the cities along the plains, the railroads fed them and kept them growing. As Stanley once said, "Without a railway . . . Congo isn't worth a penny."...

I'd always wanted to visit Lubumbashi. The very name bounced off the tongue like fingers on a drum. The copper mines, the history, the arrogant swagger from having something the others didn't. Even while supporting Mobutu's revenous hunger for decades, Lubumbashi had played second only to Kinshasa. But in the 1980s, the state-owned mines known as Gecamines (the former Union Miniere) collapsed from neglect, causing the city to finally fall on hard times like the rest of the struggling country.

But all of that changed once China came along.

With its economy growing faster than milk-weed, China had swooped into Katanga and begun hauling out commodities at enormous rates, pushing the price of copper to three dollars a pound and cobalt to thirty - the highest in a decade. China's demand for cobalt - used to manufacture rechargeable batteries in cell phones - rose tenfold from 1997 to 2005, when up to 90 percent of China's imported concentrates and ores were coming from Congo. And with the demand set high, over 150,000 local informal miners answered the call, squatting on the old government-owned Gecamines mines that had collapsed or others that were abandoned during the war. The peaceful elections also brought other companies that had anxiously been waiting in the wings. Phelps Dodge, the American mining firm, began developing a sixteen-hundred-square-kilometer, $900 million concession that encompassed two villages. Tenke and Fungurume, and sat on one of the largest copper and cobalt deposits in the world. Other companies such as Anvil Mining, from Australia, and Forrest Group, a Belgian firm, had concessions worth hundreds of millions more.

The big multinationals had to operate on the up-and-up since many eyes were scanning their affairs, especially Anvil, which had been busted several years earlier for letting government troops use their vehicles to assault a local rebel group, a battle in which many civilians were killed. These companies met regularly with aid groups and consultants about how to better serve the community. They built schools and publicized their numbers, which only accounted for about 20 percent of all mining in Katanga, a mere sliver of the money being pumped out of the ground.

The rest of the mining was illegally done by local men with pickaxes and shovels, many of them digging atop the concessions recently acquired by the big multinationals such as Phelps Dodge, which now faced the dilemma of removing them. The local miners were scattered across the province, working shirtless in their broken flip-flops and living off manioc in the sun, earning five dollars a week selling to Congolese middlemen who often disappeared on payday. The middlemen then sold the minerals to foreign trading houses and Chinese businessmen who lined the mining roads, and they in turn set the market price and made a fortune off these holes that never ran dry.

So where did all the money go? In Katanga, the ore was smuggled out in the dark of night, across the border in beds of covered trucks and railcars, past the eyes of police who hadn't been paid in months and so were hard-pressed to refuse the hush money. It went down through Zambia, Tanzania, and South Africa, where it was processed, then put into giant containers and shipped east into Asia. By the end of 2005, an estimated three quarters of Katanga's minerals were shipped out illegally, greasing the palms of government officials and police on many levels before finally hitting the sea.

The bulk of the profits from informal mining never saw the sunlight in Congo, but an estimated $37 million still trickled into Lubumbashi each month, and as a result the city became a boomtown - for some....

That same afternoon while we were walking through town, two men approached us wanting to sell us three tons of coltan. They'd dug it out of a mine eight hundred kilometers north of town and were looking for a buyer to load it onto trucks to Tanzania, then by boat to South Africa. The price was seventy-five thousand dollars.

"It's an open mine," the guy said, "and there's lots more where that came from."

"What about taxes to the government?" I asked.

"Maybe a few hundred dollars to the local chief," he said. "the government doesn't even know it exists. And we have people who can get it across the border, no problem. So are you interested?"

I told them no, and after talking to them a while longer, I learned they were both medical and law students at the local university, trying to sell blackmarket coltan just to pay their tuition. As they said, "Everyone there does it."

At breakfast the next morning at the procure, I explained the coltan deal to Leo, a Chinese miner who worked for a Canadian firm, or who lived in Canada and worked for a Chinese firm; he was never very clear, and I liked that about him.

"Seventy-five thousand dollars?" he said, tipping the jar of instant coffee into his cup, then drowning it in steaming milk. "Oh man."

I'd first seen Leo the day we arrived, walking into the procure with a group of local men, hired translators dressed in starched shirts with threadbare collars and holding clipboards. They'd disappeared into a conference room, where I could hear their conversaton as I sat reading in the courtyard outside. Leo was loud and arrogant with the Congolese, bragging in his strangled accent about how much money he was making in Katanga. "We buy twenty thousand tons of copper and ship it to warehouse in China," he said. "Twenty thousand tons. Tons! Tons! Then we sell, sell, sell! My friends, we work three months out of year, and rest of time - drive cars and lots of girls! Ha! Ha! Ha!

So at breakfast, I was anxious to hear his opinion on the coltan deal, more as just a conversation piece. He dumped six spoonfuls of sugar into his coffee and, before he could finish what he was saying held up his palm. "I explain everything after prayer." He bowed his head and his lips moved in rapid silence. He finished his prayer and looked up. "Seventy-five thousand dollars?" he said. "You get ripped off, man. I get for you much cheaper. Ha! Ha! Ha!"

An Indian named Sibu also usually ate with us. He'd been in Lubumbashi for five months but hadn't been so lucky. The day I met him, Sibu was wearing a bandage over his eye, blood still seeping through the gauze, and his cheek was purple and swollen. He'd been badly beaten by the mayor's soldiers two days before, he said, after a mining deal gone sour. He'd gotten mixed up with some Chinese newcomer looking for easy contacts and, with nothing of his own cooking at the moment, agreed to accompany the Chinese guy to a cobalt mine outside town. Soldiers stopped them on the road and asked for their mining certificates. They only had tourist visas, and an hour later they found themselves in the police station facing the commander. "We can make all of this go away for two thousand dollars," the commander said.

"It's worth it," Sibu told the Chinese guy, but he refused and demanded to see the mayor.

The soldiers brought the two men to the mayor and separated them, Sibu was a citizen of Tanzania, an African. So instead of risking trouble with the Chinese embassy, the mayor ordered his men to beat Sibu instead. Sibu eventually paid them four hundred dollars of his own money just for them to stop. The Chinese miner was released and now ignored Sibu on the streets. This was a small and not unusual price to pay for doing business in Lubumbashi, and for small-time guys, these risks were part of the gamble.

A few days later, Sibu got a job with a Canadian looking to land a contract with Gecamines, the government-mining agent. The Canadian needed someone to shepherd the process, someone on the ground who would smooth things along for a cool 10 percent. The contract was for one hundred tons of copper.

"The price on the London market is nearly eight grand a ton," the Indian said. "Multiply that by a hundred, then factor my cut." He smiled and bobbed his bloodied, bandaged eyebrows. "Not bad. Not bad at all." The contract was still tied up with the government by the time I left, and I never heard whether Sibu ever landed the big score....

The passenger train wasn't arriving for several days so we used the time to explore the station and the yard. The SNCC (the national rail company) had carefully maintained the colonial architecture of the station, everything from the cobblestone on the platforms, to the giant station clock that still kep the time, and the cafe with bonewood chandeliers draped with silver garland. In a way, the cafe itself resembled an old dining-car saloon, so cool that Lionel and I found ourselves returning there every day for beers, tall bottles of Simba that we drank slowly as the crisp Katanga breeze cooled down the night. Once the waiter even dragged a couple of beer crates onto the platform itself and let us drink there, right atop the giant copper arrow pointing north, toward where we hoped to go.

The station sat at the end of a wide cobblestone square, where three old locomotives sat high on earthen platforms like sentinels, proud trophies of the glory days. The steam, diesel, and electric engines - progressive touchstones along the time line - were painted blue and yellow, shimmering in the sun, and looking mighty. They were the first things you saw when rounding the corner from the Park Hotel, and the sight of such beautiful machines made me want to run toward them, made me want to hear the locomotive blow its high, brassy whistle, made me thirst for a cold beer in the old cafe.

Many of those same proud machines now sat idle and rusting on the rails, and the sight of them boiled the blood of Fabien Mutomb, whose office overlooked the central yard. Fabien was the director of logistics at SNCC, a company man who kept the president's stoic portrait above the calendar on his wall, but over the years he had become a dispirited patriot. He now chaired the local chapter of the opposition party, and during our regular visits that week to his office, we'd be audience to his venom-fueled soliloquies against the plague of corruption.

"How can we redevelop this country when all of its people are looking to steal?" he said one afternoon. "We have one of the biggest mining industries in the world, but no real contracts to feed back into the country. We send men to check the validity of these contracts, to weed out the fake ones, but the people we send can't even afford a bicycle ride to work. You show these men one hundred dollars and they bend like everyone else. We're talking billions of dollars in contracts. Even the mayor of Lubumbashi has a concession."

Fabien pointed out the window, where nothing had moved all morning. "I can show you what leaves this station in the middle of the night, all that cargo on its way to Zambia, and it's a scandal. I can show you what the average Congolese eats in one day, and your dog probably eats more. Years ago you could get a well-paying job here at the mines, benefits and everything. Now the dream of young people here is to make it to South Africa and wash the streets. People are now saying, 'Let's bring back the white man.' Can you believe that? 'Bring back the white man because we can't do it ourselves.' There is no more dream in this country, no more ambition. The dream here is dead."

The railroad employed thousands of people in company towns all along the line, but still owed these workers two years of back pay, and most hadn't seen a cent in months. As a result, they'd clustered in the SNCC company camps and slowly gone down with the ship....

As the sun continued to rise every morning over Katanga, the rail workers left the squalor of those company camps and returned to work, out of duty and a dog-blind faith in the boss who told them "just be patient," and from a knowledge deep in their marrow that if they ever quit, death wouldn't be far behind....

Three months later in September [2007], in Providence, Rhode Island, where Ann Marie and I had moved the preivous summer, I got an incredible piece of news. The Chinese government had announced a remarkable plan to refurbish thirty-two hundred kilometers of railway in Congo, and to construct a highway that would span the nation nearly top to bottom. In addition, they would build 31 hospitals, 145 clinics, 2 universities, and 5,000 government housing units across the country. The $5 billion loan for the project would be repaid in mining concessions, and everything, they vowed, would be completed in under three years. It was a project Leopold, Belgium, and Mobutu couldn't have imagined doing in over a century.

A new railway would connect Katanga's mines directly to the Atlantic Ocean by adding seven hundred kilometers of missing track between Ilebo and Kinshasa. That project had been part of Belgium's Ten-Year-Plan, drafted in 1952 for the long-term development of the colony, but was abandoned at independence. The existing track from Lubumbashi to Ilebo - almost a century old - would be completely overhauled, and new locomotives and railcars would be purchased. The proposed thirty-four hundred kilometers of new road would include a fifteen-hundred-kilometer highway that would barrel through the jungle, connecting Kisangani to the Zambian border in the south.

The Chinese plan for Congo would rival some of the greatest public works projects in the world, and the new road and railway alone had the potential to turn the entire economy around, connect markets, reunite families, and create jobs - even while China settled in over the mines and satisfied its growing appetite.... [end quoting from ATMFTL, by Mealer]

China in the Congo. Financial Times, Feb 9, 2009

Chinese officials like to describe burgeoning relations between Beijing and Africa as “win-win”. Africa wins from Chinese investment, infrastructure and loans. China wins by gaining access to African markets and resources to fuel domestic growth. The reality, however, is rarely so simple and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where China pitched its most ambitious African deal in 2007, all sides, now risk emerging as losers. The China-Congo deal provided for $9bn of Chinese investment in roads, railways, schools and clinics and in the rehabilitation of the mining sector. In return, Congo would cede majority rights in a joint venture to develop copper and cobalt concessions. Any difference that might emerge between the cost of infrastructure and revenues from the mines would be underwritten by the Congolese state. For the Chinese it was a classic win-win scenario. Congo is struggling to emerge from a decade of conflict and three prior decades of dictatorship. Its infrastructure and institutions are not so much in ruins as non-existent. No other investor or foreign donor has come forward with as ambitious a development programme. Nor can any other African country match Congo’s untapped reserves of base and precious metals. On paper, even if the details contain flaws, the deal could benefit Congo. If it has not turned out so, it has much to do with the toxic legacy of Congo’s relations with the west. The country is saddled with $10bn of external debt stored up from the days of Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator. It has little to show for it, and certainly no roads or schools. This was money used to appease a cold war ally long after it became clear President Mobutu was stashing it in Swiss banks. Yet Congo’s western creditors are reluctant to write it off only to see new debt contracted to China on commercial terms. The Kinshasa government is squeezed on all fronts. It has failed, through poor governance of its own, to make the moral case for debt relief, which is as strong in Congo as in any indebted African country. In the short term its finances are in desperate shape, and it must curry favour from traditional western donors. Yet China’s alternative development financing looks a more ambitious long-term bet. It ought to be possible to have both. By insisting that Congo renegotiates its deal on more favourable terms than Beijing is prepared to give, western donors risk leaving Congo with neither. Yet the bill for continuing state failure will land in Europe, not Beijing.

Rwanda's move into Congo fuels suspicion. Washington Post, Feb 13, 2009

Kigali - With thousands of Rwandan troops fanned out across eastern Congo's green hills, many residents and international observers are questioning what is really behind the operation in the mineral-rich region and how long it is likely to last....In acting now, Congo and Rwanda have in theory ended a proxy war that had played out for years in eastern Congo. Rwanda pulled the plug on rebel leader Laurent Nkunda, whom it arrested last month. And Congo abruptly turned on its longtime ally the FDLR, joining the Rwandans in an operation to hunt down the militia....But some observers see much broader economic and political motives behind Rwanda's military foray -- its third in Congo in the past decade -- that have more to do with Rwanda's regional ambitions than with the 6,000 or so FDLR militiamen. As recently as October, Rwandan officials had cast the militia as "a Congolese problem," saying it did not pose an immediate military threat to Rwanda....The stakes are high for the joint Rwandan-Congolese military offensive against the FDLR, given its potential to trigger more regional instability than it resolves. Rwanda's two earlier invasions succeeded in disrupting the militia's operations but also helped spawn more than a decade of conflict that at one point drew in as many as eight African nations in a scramble for regional supremacy and a piece of Congo's vast mineral wealth.... Many Rwandans became involved in the lucrative mineral trade out of eastern Congo after the genocide, and some observers speculate that the current military operation aims to solidify Rwanda's economic stake in the region....On that score, unverifiable rumors abound about secret deals and gentlemen's agreements struck between Congo and Rwanda over mineral rights and mineral processing. At a local level, Congolese villagers who have long suspected Rwanda of wanting to annex a swath of eastern Congo say they are certain that their tiny but militarily powerful neighbor is interested in more than disarming the FDLR. "Congo is rich," said Eric Sorumweh, who said he watched hundreds of Rwandan troops pass by his village last month. "So they just come to loot the wealth of Congo."....Kabila was politically threatened by the stunning advance of Nkunda's rebels across eastern Congo last year. And Rwanda was embarrassed by a U.N. report in December that found it to be directly or tacitly supporting Nkunda. As a result, Rwanda's prized reputation as a darling of the aid world suffered, the Netherlands and Sweden cut off aid, and international pressure mounted for the government to solve its differences with Congo. The report also found that Congo was collaborating with the FDLR. At the same time, hundreds of millions of dollars from the European Union, the World Bank and other donors -- for major road, railroad and power projects that would benefit both countries -- were largely predicated upon a detente between the two sides. That is supposed to become official when Rwanda and Congo restore full diplomatic relations, probably next month....The entry of Rwandan troops into Congo also represents the failure of U.N. peacekeepers to tame the militias and rebels of eastern Congo. A deal signed in Nairobi in December 2007 called upon the peacekeepers to assist the Congolese army in disarming the FDLR, but that effort never got off the ground....According to a U.S. official who is in close contact with the Rwandan military, the goal is not to completely dismantle the FDLR, but merely to scatter it. Several of its key leaders are not even in eastern Congo, but are living in the Congolese capital, Kinshasa, or in Europe....

Rwanda goals in Congo under scrutiny. Institue War & Peace, Feb 13, 2009 (People in eastern DRC suspect Rwanda’s real motive for intervening in the region is to exploit natural resources...Neutralising the FDLR will not be easy. The Rwandan rebels mix in the population and are organised. This makes it difficult for Rwandan soldiers to differentiate civilians from the FDLR. This military operation undoubtedly will have harmful consequences for civilians....Meanwhile, DRC is happy with Nkunda’s arrest and soon hopes to have him extradited where he could be put on trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity relating to events in Bukavu in 2004 and perhaps more recently in Kiwanja in 2008. He has denied these accusations. Some Congolese believe Nkunda’s arrest is merely a distraction, meant to conceal Rwanda’s hidden agenda to exploit minerals. It is similar to events in 1996 when the Congolese were focused on the departure of former president Mobutu Sese Seko after 32 years of dictatorship. Anxious for a new regime, many Congolese didn't suspect that Rwanda's backing of Laurent Kabila in the war that toppled Mobutu would leave it in control of the resource-rich Kivu region....)

KAGAME HELPING NKUNDA NOT and NKUNDA SAFE LIKE LUMUMBA?

Laurent Nkunda arrested in Rwanda. London Guardian, Jan 23, 2009

NKUNDA SAY CONGO OWNS RESOURCES

KABILA KILLS, RAPES & BLAMES NKUNDA

RWANDA GENOCIDE HORROR and GOMA CAMP MAFIA HOTEL

CONGO RICHES CHINA NOW and CONGO 500-POUND GORILLA CHINA

OUT OF AFRICA and CANADA GATE FOR CHINA

GOMA LUMUMBA VOLCANO and CONGO IS LUMUMBA LAND

CHINA OILS SUDAN GENOCIDE and MUGABE HAS YELLOW FEVER

AFRICA SILK ROAD TO CHINA and CHINA PUTS ON AFRICAN MASK

CHINESE TAKE-OVER and GOLDSTEIN CONSPIRACY FOR WORLD DOMINATION

Jackie Jura

~ an independent researcher monitoring local, national and international events ~

email: orwelltoday@gmail.com

HOME PAGE

website: www.orwelltoday.com